The interminable post-war period

With the Fascist military uprising of 1936, all the positive steps made towards the standardisation of Basque culture and language that had begun at the end of the nineteenth century, came to a shuddering halt. Many cultural agents lost their lives and many more were forced into exile: it is calculated that over 150,000 people left the Basque Country. A fine was imposed on anyone speaking Basque, books in Basque were burned and the persecution of the language in education, already seen in previous eras, was stepped up. This situation continued for somewhat over a decade, contributing to a major reversal in the development of the social use of Basque.

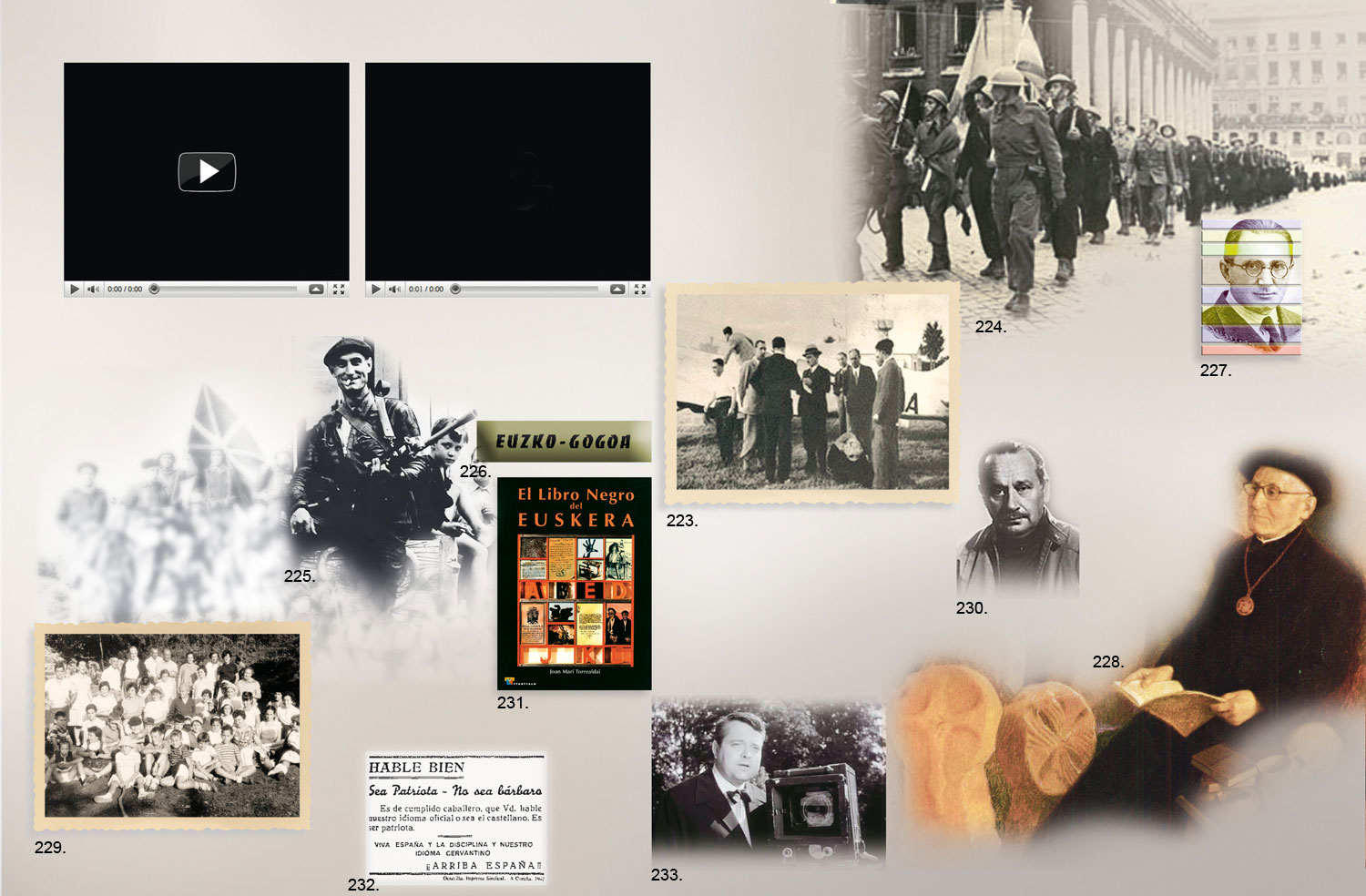

223. In the midst of the Civil War, the Basque Government was forced

into a long period of exile. It moved first to Paris, and in 1941

to New York. In 1946 it returned to France, promoting the International

League of Friends of the Basques, which managed to raise

50,000 members, defending the idea of a united federal Europe of

the Peoples. In 1951, the French Government under socialist president

Vincent Auriol, confiscated the Basque government offices in

Paris and handed them over to representatives of Franco. 224. The Gernika battalion enters Bordeaux after liberation of the

city in 1945. Following the disbanding of the Basque Army, its troops

had been posted to the ranks of the Free French army, and marched

under the ikurriña of the former Saseta battalion of the Euzko

Gudarostea. 225. Gudari (Basque soldier) at the end of the Second World War.

As they had at the end of the Spanish Civil war in 1939, many

Basque combatants who had fought with the Free French forces were

again forced into exile. North and South America were popular

venues for this new wave of the Basque Diaspora. 226. Euzko-Gogoa (1949-1959). The magazine was published in

Guatemala by exiled writer Jokin Zaitegi, with the collaboration of

another two writers, Orixe and Andima Ibinagabeitia. It printed everything

from texts on literature, music and linguistics to translations

into Basque of authors such as Sophocles, Horatio and Virgil. From

1956 on, it was published in Biarritz, and continued to have a large

number of illustrious collaborators. 227. Nikolas Ormaetxea Orixe (Orexa, 1888-1961). Poet and scholar,

he devoted his life to Basque culture, writing poems, novels,

essays and translations. Because of the richness of his Basque and

his narrative art, he was commissioned by Aitzol in 1931 to create

the Basque epic Euskaldunak (1950). Before it was published, he

was imprisoned during the war and subsequently exiled. From

France he left for the Americas, returning to his country in 1956,

when other Basque intellectuals also began to make their way back. 228. Joxe Miel Barandiaran (Ataun 1889-1991). Eminent ethnographer

and anthropologist, he was the father and pioneer of archaeological

and ethnographic research in the Basque Country. He too

was forced to flee following the fascist uprising, moving in 1942 to

Sara/Sare (Labourd) where he ran a cultural centre. In 1953, he

moved back to Ataun. By then, he was a figure of international prestige

and was running the Basque Institute of Research Ikuska (1946),

the Anuario de Eusko-Folklore (Vitoria / Gasteiz 1921) and the

magazine Eusko-Jakintza (Bayonne, 1947). He died in 1991, after a

long life, rich in research and teaching with innumerable publications

to his name. 229. The Civil War meant the end of the ikastolas; as a result, some

groups of parents organised clandestine schooling in Basque for

their children. One of the pioneers in this undertaking was Elvira

Zipitria (1906), who gave classes at her home in San Sebastian from

1943. Pictured in the photo with her pupils. In December 2009, the

Territorial Government of Gipuzkoa awarded its Gold Medal to the

group of andereñoak (primary teachers) who kept up clandestine

teaching in Basque during the post-war period. 230. After the war, Euskaltzaindia practically ceased to operate. In

the early 1950s, Resurrección Maria de Azkue resumed the work of

the Academy, with the help of Federico Krutwig. A specialist in languages

and an erudite academic, Krutwig (Getxo 1921-1998) worked

tirelessly for the prestige of the Basque language and defended

the need to introduce elements of European and classic Greek culture. 231. El Libro negro del euskera (Ttarttalo, 1998) prepared by Joan

Mari Torrealdai, documents the history of the repression and censorship

of the Basque language from 1730 and the particular severity

of the post-war Francoist period. 232. Propaganda from the fascist regime, censuring the use of any

language other than Spanish: SPEAK PROPERLY. Be a Patriot – Don't

be a Barbarian. It is the mark of courteous gentleman to speak our

official language, Spanish. It means being a patriot. LONG LIVE

SPAIN AND DISCIPLINE AND THE LANGUAGE OF CERVANTES.

UP WITH SPAIN!!. 233. Orson Welles. In 1955 Welles made two documentaries on the

Basque Country for British television. The local inhabitants – Welles

explained— speak a tongue no expert has ever been able to trace.

In General Franco's half of the Basque Country, this language is

quite literally against the law; it's treason to speak it.