gipuzkoakultura.net

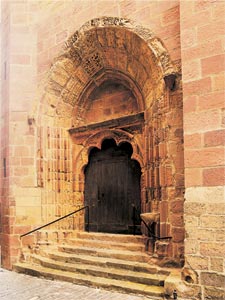

There are few mediaeval doorways in Gipuzkoa, but those of greatest quality date from the Romanesque period. In some cases, when the parish church was deconsecrated, the doorway was used as the entrance to the cemetery, as is the case with the churches of Pasai San Pedro, Azkoitia and Aretxabaleta. A common feature of all of them is the semicircular archway. Examples can be seen in Ugarte´s work in Amezketa, Garagartza´s in Arrasate, and in the La Antigua chapel in Zumarraga, dating from the mid twelfth century. The spiral on the arch in Ormaiztegi is complemented with small pointed Gothic arches, replicated in the church in Idiazabal .

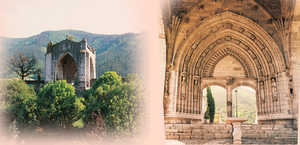

Some Gothic doorways provide evidence of how large the original churches must have been, while others are very simply and sparsely decorated, such as the doorway in Abaltzisketa. The largest of the Romanesque doorways is the one in Deba, which stands in the large cavity at the base of the belltower. The doorway in the church of St. Bartholomew's of Olaso in Elgoibar, which now serves as the gate to the cemetery, was also built at the base of the belltower. The doorway of the church in Deba is in the same style as the churches of Laguardia and Vitoria in Alava, and shows evidence of the work of two masters or workshops. The doorway of the fourteenth-century church of San Salvador in Getaria, must have been planned to be like that of Deba with archivolts, to judge from the mouldings of the jambs. The tympanum is bare of sculpture and the door cavity is framed by a garlanded arch. The parish church of Mondragon/Arrasate is equally simple: the pointed ogival shapes are a continuation of the small columns flanking the door. It is now crowned by an almost straight Renaissance arch. The only decoration is a polychrome sculpture of the Eternal Father giving his blessing, dating from the early sixteenth century The doorway of the church in Idiazabal is particularly original: it mirrors the decorative repertoire used from ancient times on prehistoric and Roman steles and ceramic pieces with perfectly carved geometric decorations and human heads. Other particularly interesting Gothic doorways can be found in Aduna and Ezkioga, Berastegi, Elduaien and Berrobi. The chapel of San Esteban was destroyed by floods in the 1950s, but the doorway is preserved in a side chapel of the parish church of Santa Maria in Tolosa.

Sixteenth century church doorways are neither the most impressive nor the most plentiful features of the Renaissance period in Gipuzkoa. As we have mentioned, greater attention was paid to erecting the monumental churches we see today. Two doorways were added to Gothic structures: that of the Bidaurreta Convent in Oñati whose arches and niches lie halfway between Gothic and Renaissance architecture; and that of the parish church of Hondarribia (Fuenterrabia), dating from 1566, which built entirely in the Renaissance style, enclosed within an archway of caissons, with the two doors well integrated by the fine uninterrupted mouldings. Among the churches built or restored in the first half of the sixteenth century is the northern doorway of the church of Eibar, on which the date of erection (1547) is inscribed. It is noteworthy for its luxurious Plateresque carving. The church of Aitzarna has a particularly elegant and harmonious doorway, divided into two doors beneath thick archivolts. The breadth and meticulous construction are unusual among rural churches.

Seventeenth century church doorways in the province tend to be bare and austere. They are the result of a time of clear economic crisis, which led to cutbacks in the building boom of the previous century. The force of tradition meant that models consolidated in previous eras were repeated, but these were gradually changed as artists took new liberties and applied their own fantasies to the work.

The first commissions were relatively insignificant, consisting merely of adorning the entrances to the churches with simple mouldings containing arrangements and features that were reminiscent of works produced by Juan de Herrera, and specifically the Escorial. His doors generally have lintels, like that in Zumarraga, or arches. On either side pilasters were erected and where there was decoration, it consisted of pyramids with balls or acroterums like the one in Urrestilla; a cross in the centre or a console similar to the leather ones with their curled edges. The rigidity and flatness of all the features is only relieved by the top part in the form of a pediment, which in many cases is broken at the top with thick spirals. Examples can be seen in the side door of the church at Eibar and in Zizurkil, where there is a small sculpture on a pedestal. The classic column support can be seen in some doorways underlining entrance arches. These structures are not as flat as the others, since the columns and their pedestals have been brought forward. We find this design in Getaria, in a version with twin Ionic columns with fluted torch-shaped shafts and strong mortisework on the pedestals. Austere design concepts in which architecture prevailed over decoration held sway until the last third of the seventeenth century, when the compositions were still identical to those of sixty years before; but as time went by, the motifs again became more prominent, with greater relief, and thick mouldings were used, superimposed to give a multiplying effect. Example can be seen in Albiztur and Beizama.

A new type of doorway was developed in the churches of some convents. This consisted of a rectangular-shaped facade, with arches at the bottom, topped by a triangular pediment. It is based on models from Carmelite churches. This was the design used in the Bernardine and Carmelite convents in Lazkao and the convent of La Concepción in Segura. The Franciscan convent in Tolosa has a doorway in the Escorial style with no pediment. In sanctuaries and churches too we can find the style that the architect Vignola had popularised in Rome: a low body and an attic joined by spirals or orillions. This is the design used in the doorway of the Basilica of Dorleta and in the church in Alegria.

The prototype of facade in which the bell-tower is adapted or serves as a doorway can first be seen towards the middle and end of the seventeenth century, in a number of designs which were not eventually implemented, by architects Martín de Aguirre and Lucas de Longa. It was not until nearly the mid eighteenth century before this type of design was used in the church in Elgoibar by Ignacio de Ibero, in Andoain and Usurbil by his son Francisco and later in Eskoriatza, Aretxabaleta and Ibarra by Martín de Carrera.

Tomás de Jáuregui designed the doorway of the church in Tolosa in such a way as to avoid blocking the view of adjoining buildings. It takes the form of a ìstumpî or fragmentary development of the bottom section of a tower.

In many churches in Gipuzkoa the doorway is sheltered under a large arch to protect worshippers from the elements. Examples of this style can be seen in the parish churches of Pasajes de San Juan and Errenteria, attributed to Gómez de Mora; in Segura the doorway is more Baroque, with bulging chiaroscuro decoration. Greater depth was introduced into this design in the eighteenth century, when instead of an arch the doorway was placed in a large recess or gigantic niche, like a triumphal arch. The doorways at Hernani, Azkoitia and Zegama all follow this design, and are topped with a pedestal as a curtain to hide the wall behind, like in Oñati. A variation can be seen in the Church of Santa Maria in San Sebastian, where the doorway is framed between two square towers on either side. Another novel arrangement was used in the Sanctuary of Loyola, where the doorway encloses the outline of the church like a semicircular belt.

The finest examples of neo-classical facades in Gipuzkoa all share an important urban significance, accentuated by their porticos or narthexes of arches and their staircases. One of the generation of architects who forcibly introduced this style was Ventura RodrÌguez, who designed the doorway of the parish church of Azpeitia, built by Francisco de Ibero, and designed horizontally as a classical portico. The doorway of the church in Elgeta uses the same language and has a strong monumental accent, embracing the tower and church on the front and sides, with a huge portico fitted with arches and windows. The doorway of the church in Usurbil is similar in style but not as high or large on the epistle side of the building. The really innovative experiment in this style came from Silvestre Pérez with the church in Mutriku, where the portico is structured almost independently, with a surprising clarity of volumes.