gipuzkoakultura.net

As we have mentioned before, this cave was discovered by two young men from Azpeitia; Andoni Albizuri and Rafael Rezabal. Having located the small cave in the area – the existence of which was already common knowledge – they arranged to meet one Sunday to examine the cave and see if it contained any remains.

As they were preparing their investigations, they noticed cold air coming out of a small hole. They managed to widen the hole just enough to allow them to crawl in. They slithered along the ground for about 20 metres, after which they found they were able to stand up. Having made sure that the ground they were walking on – covered by a mantle of stalagmites – was firm enough, they advanced along the gallery, which got progressively wider. The stalagmitic film crunched beneath their feet. The gallery was completely untouched. They were the first people to enter it in millennia.

They continued along the gallery until they came across a large panel of horses. Such was their excitement that they were unable to continue surveying the cave and decided to make their way out again.

That afternoon, they informed José Miguel de Barandiaran of their discovery, and the next day, Monday, they told me.

On Tuesday Barandiaran and I visited the cave with the two discoverers and on Thursday, before the news had spread, an iron gate was fitted over the then small entrance. As yet, the cave still had no name and so we decided to call it after the hill in which it stands, Ekain.

Twenty days later, we began the first survey of the sanctuary, and the results were published at the end of 1969 in Munibe.

We also took samples from the vestibule of the cave, the task Andoni and Rafael had left incomplete to explore the hole leading to the interior. These samples proved positive, indicating the existence of a prehistoric site.

Following the discovery, a whole series of problems and bureaucratic battles arose between the public authorities and the Prehistory Department of the Aranzadi Science Society. These were the years of the great Spanish tourist boom, when all too many sacrifices were being made for quick profit. Nearly 200,000 people were being admitted to the Altamira caves every year, and the cave was being exploited - in the worst sense of the word - for the sake of tourism.

The authorities wanted to do the same with Ekain.

The Society’s Prehistory Department was directly opposed to this idea. However, tourism was a much more powerful force and in the political regime of the day it held all the aces. The press accused the Aranzadi Science Society of wanting to lock culture up behind bars and demanded that it open the cave to the public immediately.

The Aranzadi Science Society, which since its foundation in 1947 had been in charge of looking after the prehistoric heritage of Gipuzkoa, had difficulty preserving this cultural asset, so extraordinary and yet so fragile. They argued that opening it to the public might sate the curiosity of some and fill the pockets of others, but would deprive future generations of any knowledge of the cave. Despite their arguments, the post of commissariat of archaeological excavations of the Province of Gipuzkoa, held by the Society until that time, was taken from it by the Spanish Ministry of Education.

The society was, however, allowed to schedule excavation of the site, and for this purpose it requested that the cave should remain closed for the time being, since it would be impossible to excavate the vestibule if visitors were constantly walking through it to get to the interior. This first step was achieved successfully and excavations began that same year (1969) and were not completed until 1975.

By then, public opinion had shifted. The damage caused by excessive visitors to the caves of Lascaux and Altamira was well-known. In addition, progress towards the establishment of democratic conditions following the death of Franco and the establishment of a pre-autonomous system in the Basque Country, made it possible to keep the cave closed. The worst had passed.

Since then, the Aranzadi Society, through its Prehistory Department, has jealously guarded this magnificent heritage. As a result, the cave remains in exactly the same condition as it was when it was discovered – just as it had stood for many centuries before.

The town council of Zestoa is currently building a replica of the cave, which will serve an educational function without jeopardising conservation of the cave itself.

As I have already said, at the entrance to the cave there is an archaeological site whose excavation has given us an insight into the life of the artists who decorated the cave. Beneath the Magdalenian archaeological levels there are significant levels filled with the bones of cave bears. We may therefore assume that these animals occupied the cave before the Magdalenian human groups arrived and hibernated by the hundred inside. This can be seen in the way protruding rocks have been rubbed smooth in many of the narrow passageways in the cave, and by the hibernation pits in which they curled up to sleep through the winter. During that period, the entry to the deeper galleries at Ekain gradually became blocked off.

In order to get to the inside of the cave, to the deep galleries that being on the right of the entrance, the Magdalenian cave dwellers had to crawl along a narrow path for a space of twenty metres. Only then could they straighten up and walk upright through the rest of the cave.

The first figure in Ekain – a large horse’s head – stands about 50 metres from the entrance while the furthest figures are more than 150 metres from it.

We will start by examining that large horse’s head. It is situated on the roof of a small vault, next to a point at which a side gallery leads from the main one. It would seem to be meant to announce that Ekain is the cave of the horse par excellence. A little further on, in Erdialde – the central more spacious area of the cave – there is a large natural rock formation which looks very like a horse’s head. The palaeolithic artist, who saw animals which he then completed in many of the rocky edges, cracks and protrusions on the wall, where we can make out nothing, must necessarily have seen this naturally-formed head. It is possible to make out ears, an eye, the mouth, and the nasal orifice. The latter appears to have been artificially sculpted, although we cannot be entirely sure. In any case, under this rock the artist of Ekain painted a small horse’s head on one side and on the other, a bison – a complement to the horse in palaeolithic art. Perhaps this natural rock was the inspiration which made the decorators of the cave dedicate it to the horse. The first figure, the large horse’s head - the largest head in the cave, would appear to corroborate this idea.

The small side gallery which runs from the site of this painted head contains, among other figures, a salmon. The artist used a rocky edge, which forms the front half of the back and one of the many small depressions in the rock to make an eye. He then completed the figure in black paint, with the rest of the outline, the mouth, the line of the gills, the fins and the lateral stripe – the line of special scales running down a fish’s flank.

At the end of this gallery there is a cave bears’ hibernation pit and the projecting rock has been worn down by the hundreds of animal who rubbed against it as they made their way uncertainly into the place.

If we go back to Erdialde and at the point of access to the large sets of horses, we find bison drawn on either side of the gallery. The one on the right as we go in makes use of a rocky edge and a crack. Lit from above these look like a bison’s back with its tail. The artist completed the figure by painting the head in black, with the horns and jaw line, the hair hanging from the throat, the line of the abdomen and the legs.

This is another example of what is known in modern art as “art trouvé”; the use of natural shapes suggesting, in this case, the shapes of animals, which are then formed and styled by the artist into that animal shape, as we have also seen in Altxerri.

Opposite this bison there is another, also painted black, which is missing the line of the back. A crack in the rock at the height of the hindquarters may indicate the beginning of the hump. In contrast, the tail, the abdomen and legs are clearly depicted in detail. The head is today more faintly represented than the rest, but the horns and chin can easily be made out.

The legs have been drawn with particular care and the perspective of those on one side and the other has been well executed, crossing or not crossing the back of the abdomen line.

The legs have been drawn with particular care and the perspective of those on one side and the other has been well executed, crossing or not crossing the back of the abdomen line.

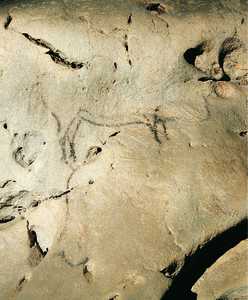

Following the two bison there are several groups of horses. This is the Zaldei gallery. On the left-hand side there is a set of eight horses, with eleven more on the right. Amongst those on the left, one is particularly striking and has been painted in great detail. It has been executed in black paint with plain dye filling certain areas of the body.

The head is separated from the neck by a line. The mane stands erect, as it does in the Przewalski horse, the only wild horse still in existence whose coat or markings contain features also to be found in the Ekain figures. The erect mane is sometimes represented by means of a continuous line from the ears to the withers and sometimes by means of short vertical lines, like those in the horse below, described here.

Another feature of wild horses is the dark colouring of the neck and the ends of the legs. There is also an M-shaped line on the flank of many of the Ekain horses.

Opposite this group is the great panel of Ekain, described by Leroi-Gourhan – the maximum authority on cave art of his time – as “the most beautiful panel of horses in all Franco-Cantabrian art”. It would appear to have been created by the same hand, among other reasons because of the care that has been taken not to superimpose one figure on another. This contrasts with many other palaeolithic panels, specifically in Altxerri.

Following a deer situated on the left, the panel begins with three bison, one of which has been coloured red. There are then eleven horses, a fish shape and a red curve, which appears to mark the end of the group, or a link to another one (described below).

At the top right of the panel there is a red-painted bison, with a raised tail. The back legs have been left unfinished, so that they will not overlap with the hindquarters of the red horse situated behind and below. The colour comes from limonite, a natural iron oxide mineral.

Behind it there is another bison in black and below them a magnificent horse painted in black and red, accompanied by carving. Once again we see the series of details we have observed in other horses and among wild horses: an erect mane –depicted here by means of a continuous line – zebra-like stripes on the neck, an M-shaped line on the flank, etc. It is particularly interesting to note how the shaggy hair on the belly has been depicted, using small vertical strokes, the only case of its kind in the Ekain cave.

We could continue describing all the other horses individually, but we shall limit ourselves to just two more: one in the bottom centre and another on the lower left.

The red horse has the finest front legs of all the horses in the cave. The head – outlined in black paint - is magnificently drawn. The muzzle has been carefully depicted by means of an inflection, behind which a small curving stroke has been drawn to indicate the edge of the nasal passage. The mouth is represented by a line. The erect mane is depicted with short vertical strokes, and from it extend a number of zebra-like lines covering the neck.

The front legs contain some magnificent details: the knees (or wrists), the fetlocks and the hooves. There are also zebra-like transverse lines on the shoulder, as sometimes seen on wild horses.

In front of this horse there is another smaller one, in an inclined position, which is simplicity itself. Note the way its front limbs have been painted. In contrast to the details of the previous figure, here the legs have been stylised, and end in a point, but the knees have been given a simple and very beautiful inflection.

None of the figures in the panel overlap. At some later date, however, a bison was carved over some of the horses in the centre of the panel, although today it is difficult to make it out.

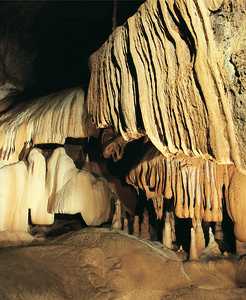

Opposite this large panel there is a hall filled with cascading stalagmites, columns, concretion folds and a few figures.

If we move further through the gallery, we come to a small open area (Artzei), also filled with stalactite and stalagmite formations, in one of whose low ceilings a pair of bears are depicted, which can only be seen from a crouching position.

The two consist of simple silhouettes painted in black with a wide stroke. The paint appears to be have been smudged, extending beyond the original lines. The small bear is complete. The larger one is missing the head. Its tail, however, is better defined. There is a paint mark in line with its heart. The thick, dense fur of these animals does not allow the same anatomical detail that we have observed in short-haired animals like horses. But its outline, the width of its legs, the short tail, the development of the loins, etc. leave no doubt over its identification.

We can even be more specific and exclude the cave bear, which had had a very well-developed hump-like withers region, but low loins.

The paint used to depict the bears is different to that of the other figures. For the other figures, the artist has used sticks of charcoal taken from the fire at the entrance to the cave. For the bears, however, he used a manganese oxide mineral, an important seam of which runs along the wall of the cave just before Artzei.

Moving through the cave through a more difficult area, we come to Azkenzaldei, where we find the last horses - a set of seven animals. They are all, without exception, facing towards the exterior of the cave; in other words, towards the area where the bears are found.

The first horse is preceded by a curved line, which appears to indicate the start of the figures, or to relate this point with the end of the large panel, at the end of which there is an analogous line. This first horse is a silhouette in black with some plain dye in the middle of the back. No eye has been depicted and the legs are unfinished. Like many of the horses in the cave, the front of the torso is hypertrophied, with the hindquarters set back and the rump exaggerated.

To the left of this horse, beneath a spacious vault, there are another six. One of these is particularly striking for its workmanship, and because of a carved area it contains. The figure is executed in a black line encircling the entire outline of the animal and also containing certain details. The mane is very well marked with a continuous line and runs between the ears like a toupee. The neck has four zebra-like stripes. The M-shaped line on the flank is also clear.

Inside and around the horse there are various carved lines. One of these is arrow-shaped and is pointing at the animal’s heart.

From here on, the cave is impassable.