THE 18th CENTURY

French attacks

The century began, as usual, with attacks from French corsairs. In spite of the fact that a frigate had been built in Bilbao in 1692 to defend the entrance and exit of ships from the Abra Estuary, ships were still being plundered in these waters, since the corsairs respected neither the authorized ships nor those of friendly nations. In 1709 and 1710 some ships were attacked when setting out for England and Ireland equipped with the corresponding passports, falling into the hands of French corsairs at the very outlet of the port. Protests from the Consulate brought no results.With respect to our ships, we have isolated information about how, for example, Juan de Zurriarain from Amezketa, died on a corsair vessel in 1712.

We also know that the Gipuzkoan Delegation went to the King about the "San Julián" case. This boat, which had previously belonged to people from Donostia-San Sebastian, was always robbing thoughout Europe with another name, under the command of a French corsair. As the letter from the Consulate to the Delegation stated, "through swindling and double dealing with the captain and other people, using a flag which they state to be Dutch, hiding that of its nation and the name of the ship".

Basque-French privateering reached extraordinary heights during this period, and especially during periods of war, such as the Seven Years’ War, when they were a worry to England, and later during the USA’s War of Independence.

98. Espadas de taza y de concha del siglo XVII.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

99. Blas de Lezo, se destacó en sus ataques a los piratas que atemorizaban a los buques españoles de las Antillas.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

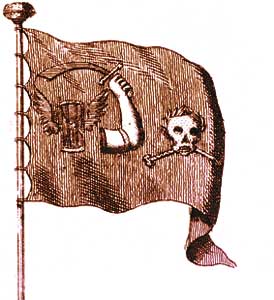

100. La bandera de la calavera y las tibias, la conocida "Jolly Roger", no fue la única utilizada por los piratas de la "Edad de oro de la piratería" (siglos XVII y XVIII). Muy a menudo las personalizaban con motivos como relojes de arena, gotas de sangre, flechas, espadas... Pero muchas veces, para actuar con mayor posibilidad de sorpresa, los barcos piratas enarbolaban falsas. También eran utilizadas las banderas lisas, cuyos colores tenían valor simbólico: negro de muerte, rojo para la batalla sin cuartel, etc. ("La Connoissance des Pavillons").

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Attacks in the Caribbean

Crossing over to the other side of the Ocean we can see that, at the beginning of the century, the Spanish Crown was incapable of surveilling trade with its colonies, and these in turn, rich and developed, had no means of transporting their products to the metropolis. This, together with the Dutch, French and English who had rushed to take power of small Caribbean islands so as to control the area, led to Venezuelan trade being monopolized by foreigners.But some Basque seamen couldn’t resign themselves to this fact and would confront the danger of daring to trade on these coasts. Some, such as the Captain Manuel de Iradi, saw his frigate, called "Jesús, María, José and San Sebastián" no less, being boarded in 1711 by an English corsair, which he was able to fight off with three volleys of artillery and musketry, in this way saving his important load and the voyagers he was transporting.

Philip V then tired to promote overseas trade, forbidding the introduction of any product from America which was brought in by foreign hands and reducing their right to traffic with cocoa by more than a half.

Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas

In 1728 Philip V granted Gipuzkoa the permission to form a Company, which shared its trading profits with the Crown.On the 25th September 1728, a treaty was signed between Spain and Gipuzkoa and, two years later, the first ships left Pasaia for Caracas.

The Spanish Crown obtained, through the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas, the security of protecting the coasts of Venezuela from attacks by foreign corsairs and pirates. The Company’s ships were armed, which meant that they could dedicate themselves to privateering without abandoning their commercial activities. The Company’s corsairs were greatly feared and mainly attacked English and Dutch ships trading illegally.

The Company revolutionized the economy of the province. It took time to get off the ground, until the Gipuzkoans won the trust of the Americans and removed the Dutch from the trade. The benefits didn’t take long to appear in the ports of Pasaia and Donostia-San Sebastian, and were also reflected in the construction of ships, which was continuous.

The maintenance of this trading line required corsairs to guarantee the possibility of its development. Even moreso in the times between 1740 and 1748, when the war of Austrian succession made Spain and England into enemies.

The Basque corsairs became a thorn in Great Britain’s side, and the latter’s corsairs became the natural enemy of the Spanish Fleet, which had regained the level of respect it had enjoyed during the era of the Austrias.

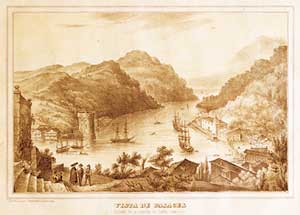

101. En 1730 salieron las primeras naves de la Compañía rumbo a Caracas.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

102. Nuestra Señora del Coro, fragata armada en corso por la Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Returning to our corsairs, and mainly to the service of the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas, of which we have continuous news during these years. Ships such as "San Ignacio", known as "La Peregrina" ("The Pilgrim), or "Nuestra Señora del Coro", "Esperancilla" or "San Juan Bautista", manned by seamen from Ataun, Portugal, Tolosa, Normandy, Extremadura, Villabona, Basque-French and even priets from Donostia-San Sebastian, were a continuous source of information during those years when English prisons were full of Basque corsairs, and the Gipuzkoan coasts became used to seeing its ships bringing back English prisoner ships, loaded with merchandise, such as in April 1744, for example. On this date there is proof that two English ships were taken prisoner, the first with thirty tons of copper and around the same amount of oil, almonds, raisins and Moroccan leather, all worth eighty thousand "pesos", and the second with four-hundred-and-fifty ready-made outfits.

Logically, and moreso in companies of this type, risks were not limited to defending oneself from the "official" enemy. They had to be on the outlook for any danger. So, in 1747, the "Ana Margarita", a Dutch ship bringing provisions to Donostia-San Sebastian, which had arrived to the entrance of the port, and had the coastal pilots at its side, was taken by a corsair xebec from Bayonne which took it to its own city, infringing the existing agreement.

The "Casa de Contratación" and Consulate of Donostia-San Sebastian wrote a letter to the province’s delegation in which, among other problems suffered by seven Spanish ships in the port of Bayonne, he states that..."the coasts are full of English corsairs" and, by way of proof that "the natives of this province have not lost their courage" he communicates to the King that the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas "has armed one of its smaller ships for sailing to the port of Guaira".

They took two days to prepare this ship before it left armed with twenty cannons and manned by sixty men, determined to defend it to the end. In addition, in the same letter, he says that "a corsair vessel is to be built by certain individuales who will arm it and, in honour of Your Majesty, use it to go after your enemies".

Logically, and moreso in companies of this type, risks were not limited to defending oneself from the "official" enemy. They had to be on the outlook for any danger. So, in 1747, the "Ana Margarita", a Dutch ship bringing provisions to Donostia-San Sebastian, which had arrived to the entrance of the port, and had the coastal pilots at its side, was taken by a corsair xebec from Bayonne which took it to its own city, infringing the existing agreement.

The "Casa de Contratación" and Consulate of Donostia-San Sebastian wrote a letter to the province’s delegation in which, among other problems suffered by seven Spanish ships in the port of Bayonne, he states that..."the coasts are full of English corsairs" and, by way of proof that "the natives of this province have not lost their courage" he communicates to the King that the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas "has armed one of its smaller ships for sailing to the port of Guaira".

They took two days to prepare this ship before it left armed with twenty cannons and manned by sixty men, determined to defend it to the end. In addition, in the same letter, he says that "a corsair vessel is to be built by certain individuales who will arm it and, in honour of Your Majesty, use it to go after your enemies".

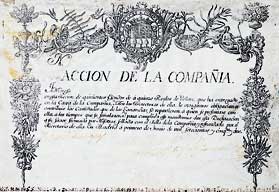

103. Acción de la Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

104. Rincón de Pasajes. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

The "Casa de Contratación" and Consulate of Donostia-San Sebastian wrote a letter to the province’s delegation in which, among other problems suffered by seven Spanish ships in the port of Bayonne, he states that..."the coasts are full of English corsairs" and, by way of proof that "the natives of this province have not lost their courage" he communicates to the King that the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas "has armed one of its smaller ships for sailing to the port of Guaira".

They took two days to prepare this ship before it left armed with twenty cannons and manned by sixty men, determined to defend it to the end. In addition, in the same letter, he says that "a corsair vessel is to be built by certain individuales who will arm it and, in honour of Your Majesty, use it to go after your enemies".

The Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas ended up with had fifty ships, most of which had the names of saints, with exceptions such as "Hermiona" and "Amable Julia" (Kind Julia). Some had nicknames by which they were better known, such as "La Peregrina", "El Pingue", "La Chata" or "El Caballo Marino" (The Sea Horse). They transported passengers, mail, books and all kinds of merchandise. It can be said that they were the only means of permanent communication between Europe and America.

But signs started appearing of oncoming decadence. The Royal Decrees of 1776 and 1781 constituted the creation of similar companies, whose rights were similar to those of the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas. And in 1785, the Real Compañía de Filipinas was founded.

This is the end of the life of the “Compañía” (1728-1785), which covered the most hazardous years of Venezuelan colonial history. By way of an epilogue we would say that it reestablished contact between the two worlds and, as well as commercial dealings, it meant a means of exchanging ideas. It was not by chance, therefore, that Venezuela was the focal point of liberal and emancipating ideas in the Colonies.

For Donostia-San Sebastian this meant that city life was greatly improved, bringing a period of well-being. However, among its dark moments, was the acceptance of slavery

They took two days to prepare this ship before it left armed with twenty cannons and manned by sixty men, determined to defend it to the end. In addition, in the same letter, he says that "a corsair vessel is to be built by certain individuales who will arm it and, in honour of Your Majesty, use it to go after your enemies".

The Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas ended up with had fifty ships, most of which had the names of saints, with exceptions such as "Hermiona" and "Amable Julia" (Kind Julia). Some had nicknames by which they were better known, such as "La Peregrina", "El Pingue", "La Chata" or "El Caballo Marino" (The Sea Horse). They transported passengers, mail, books and all kinds of merchandise. It can be said that they were the only means of permanent communication between Europe and America.

But signs started appearing of oncoming decadence. The Royal Decrees of 1776 and 1781 constituted the creation of similar companies, whose rights were similar to those of the Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas. And in 1785, the Real Compañía de Filipinas was founded.

This is the end of the life of the “Compañía” (1728-1785), which covered the most hazardous years of Venezuelan colonial history. By way of an epilogue we would say that it reestablished contact between the two worlds and, as well as commercial dealings, it meant a means of exchanging ideas. It was not by chance, therefore, that Venezuela was the focal point of liberal and emancipating ideas in the Colonies.

For Donostia-San Sebastian this meant that city life was greatly improved, bringing a period of well-being. However, among its dark moments, was the acceptance of slavery

105. Baiona fue un activo puerto corsario durante toda la historia del corso vasco, incluso cuando ya éste comenzaba a declinar.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

106. Grabado de la desembocadura del río Deba.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Ultimos corsarios

Pero la ingerencia creciente y más minuciosa de la Hacienda iba poniendo trabas y quitando rentabilidad al negocio del corso. En 1779 el Consulado de San Sebastián, propone por última vez armar un navío corsario.En 1779 Deba se queja de que una pequeña embarcación corsaria inglesa merodeaba por sus costas, no disponiendo la villa de "cañón alguno", estando indefensa y sin pólvora. El comandante general de la plaza de Donostia, marqués de Bassecout, habla, también por estos años de "los corsarios enemigos que infestan estas costas". Y también se queja de la carencia de medios de artillería.

En 1783 España e Inglaterra, que volvieron a enfrentarse en este siglo, esta vez por el apoyo español a la independencia de EEUU, tras algún que otro desastre marítimo, lograron al fin firmar la paz.

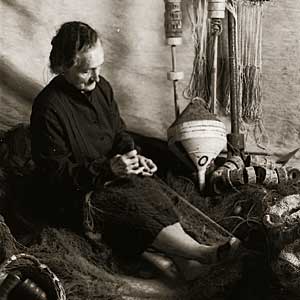

107. La vecindad de la costa ha definido siempre el carácter de las actividades de sus moradores.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

108. Los corsarios vascos forman ya parte del recuerdo.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Y aquí empieza a desvanecerse el mundo corsario que nos ha ocupado y que más aún ocupó a nuestros antepasados durante siglos.

Sin embargo, al otro lado de la frontera, es precisamente a fines del siglo XVIII cuando aparecen las últimas grandes figuras del corso vascofrancés. Son figuras aisladas, nacidas para la vida de combates y aventuras novelescas, cuyas vidas parecen, a juicio de Iriart, sacadas de las páginas novelescas.

Sin embargo, al otro lado de la frontera, es precisamente a fines del siglo XVIII cuando aparecen las últimas grandes figuras del corso vascofrancés. Son figuras aisladas, nacidas para la vida de combates y aventuras novelescas, cuyas vidas parecen, a juicio de Iriart, sacadas de las páginas novelescas.

109. Pasajes.© Joseba Urretabizkaia

110. Algunos personajes guipuzcoanos navegaron en embarcaciones piratas extranjeras. Tal es el caso del alguetarra Joaquín de Iturbe, "Joaquín Xantúa", célebre bandolero que en su juventud fue pirata o corsario y navegó en dos cañoneras francesas. Terminó recluído en 1799 en el Castillo de la Mota de Donostia.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Ichetebe Pellot nació en Hendaya en 1765 y sus hazañas se extendieron por todos los océanos. Era reconocido por sus tretas, astucias y osadía.

Siguiendo la tradición de los piratas y lobos de mar de la literatura, casi siempre mutilados, tuertos y renegados, encontramos a Destebetxo, nacido en Donibane Lohitzun. Fue una pura cicatriz todo él, además de enjuto y feo y un indiscreto cañonazo le hizo la cirugía, amputándole las dos posaderas. Actuó sobre todo en aguas del Golfo de Bizkaia.

El filibustero Nicolás Juan de Laffitte nació en 1791 en Baiona, o en Ziburu, según otros. Tuvo su cuartel general en Nueva Orleans y fue en América donde desarrolló sus actos.

Siguiendo la tradición de los piratas y lobos de mar de la literatura, casi siempre mutilados, tuertos y renegados, encontramos a Destebetxo, nacido en Donibane Lohitzun. Fue una pura cicatriz todo él, además de enjuto y feo y un indiscreto cañonazo le hizo la cirugía, amputándole las dos posaderas. Actuó sobre todo en aguas del Golfo de Bizkaia.

El filibustero Nicolás Juan de Laffitte nació en 1791 en Baiona, o en Ziburu, según otros. Tuvo su cuartel general en Nueva Orleans y fue en América donde desarrolló sus actos.

111. Ichetebe Pellot. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

112. En Baiona y en Donostia algunos nombres de calles guardan el recuerdo y la evocación de los corsarios vascos.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

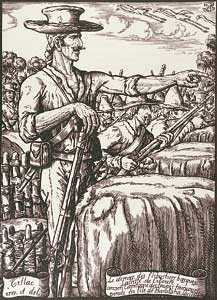

113. Nicolás Juan de Laffitte. (Dibujo de P. Tillac).

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

El final

En 1802 la Ordenanza de Matrícula dispuso que "para que una embarcación, pueda armarse en corso, ha de preceder aviso del Comandante de Marina", con lo que se perdía el aliciente de lo imprevisto.Sin embargo, hasta que no se firmó el "Tratado de París" en 1856, las patentes de corso, que habían estado mucho tiempo sin usarse, no fueron definitiva y oficialmente suprimidas.

Los hombres de nuestros muelles, tuvieron que limitarse a las actividades que nunca habían abandonado del todo y en las que también eran unos expertos.

El norte del destino es irreversible. Los tiempos modernos han venido a rubricar la esquela de nuestros antiguos corsarios.

114. Arreglando las redes. © Joseba Urretabizkaia