LIFE ON BOARD

The crew

The most important crew member of a large corsair ship was that of the captain who played the role of middleman between the shipowners and the crew members. He was the one who decided whether or not enter into combat and was in charge of discipline on board. The lieutenant captain would substitute the captain in case of his illness or death and would stand a round of guard. The frigate master supervised the nautical steering and administered the provisions. The pilot directed navigation and gave orders to the helmsmen. The Boatswain directed the carrying out of the captain’s orders and was in charge of the rigging and protection against fire. His assistant was the guardian who was in charge of cleaning the ship, the smaller boats and the cabin boys. The crew was split into three categories: the seamen, the cabin boys and the boys; the first two looked after the sails and navigation in general and the third were in charge of cleaning, food, strands for rope and the prayers on board ship. In addition to these were the constable, who was in charge of the artillery, the artillerymen, the soldiers for boarding, the carpenter, the chaplain, the clerk and the surgeon. There were two other typical jobs on corsair ships: that of officer in charge of prisoners, who would govern the captured ship until reaching port and sell it, and the frigate supervisor, who controlled everything which took place during the voyage, the behaviour of the crew and avoided fraud.

48. Bayonne. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

49. The corsairs would keep their belongings in a chest. This example belonged to a corsair and is now in Biarritz museum.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

50. Basque corsair

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

On simpler ships, this crew was reduced to the essential members.

The crew were either local or from the surrounding areas. They would sometimes come from other parts of the province or even from outside it. Some were even foreign, such as French, Flemish or Irish, although it this wasn’t customary. The pilot was often French, for working in the French area and because most Basque-speaking seamen were more experienced with the rigging and rope than they were at piloting. Hardly any of them understood Spanish, while the more experienced sailors were bi-lingual. They came from low social classes and only a minority knew how to write.

The crew were either local or from the surrounding areas. They would sometimes come from other parts of the province or even from outside it. Some were even foreign, such as French, Flemish or Irish, although it this wasn’t customary. The pilot was often French, for working in the French area and because most Basque-speaking seamen were more experienced with the rigging and rope than they were at piloting. Hardly any of them understood Spanish, while the more experienced sailors were bi-lingual. They came from low social classes and only a minority knew how to write.

Life on board

The day-to-day life of any Basque corsair or sailor on a ship passed as follows:The crew lived on the deck. There were normally several watches throughout the day lasting four hours each. Work started at sunrise: keeping the decks clean, checking and hoisting the sails, climbing up the masts and tying the ropes. Every half hour a cabin boy would sing the time, accompanied by a Pater and an Ave Maria. Every morning each sailor would roll up the mat or blanket where he had slept, pull on his clothes, wash himself in a bucket, eat a frugal breakfast (cake, biscuit, garlic, cheese and a few grilled sardines), throw out the water which the ship had taken in during the night, and organize his trunk or chest. This box contained the clothes of any corsair or sailor, comprising a woollen vest, blouse, breeches, cloak or cowl, perhaps a short cape and a hat. They each dressed as they wished and only Basque-French sailors introduced a uniform as from the 17th century. The captains and officers dressed with more elegance. To satisfy their bodily needs, they would defaecate or urinate over the sea, to do which they would hang from the rigging or plank hanging over the waves which was called the "Komunak" (toilets) or "the gardens".

51. A pack of cards from the house of J. Barbot. Donostia-San Sebastian, 18th and 19th centuries.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

52. Kitchen utensils used on board corsair ships were very similar to these.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

The only decent hot meal they had was lunch, and there was a sailor or cook who would prepare food in huge iron cauldrons, set over an open fire. Food was plentiful but monotonous. It included oil, garlic, beans, runner beans, chick-peas with cured meat, bacon, salted cod or sardines, salted meat, wheatcake or biscuits, all of which was stored in the driest part of the boat. Honey substitued sugar and wine was rationed per man and day since it was expensive. They each received their ration in a clay bowl or wooden plate; with a wooden spoon and a dagger completing their utensils. Lunchtime was a moment of great hullabaloo.

They also slept on the deck, each in their own space. Only the captain had his own cabin, and even then only during the last centuries of privateering. Moreover there were no beds, only hammocks.

There were also night watches prior to which prayers would be said. Every following half-hour a ritual song was sung and each hour the helmsman and watch were changed.

The lack of hygiene, crowding on the deck and monotonous food were an excellent hatching ground for illness. Bad nutrition meant that the seamen had hardly any resistance to illness, and the danger of death through an epidemy on the ship was rife. The most common, illness was scurvy, still to be discovered, which was caused by the lack of vitamins. Only the officers had their own personal provisions (figs, sultanas, marmelade, grapes,...) with certain amounts of the necessary vitamins. Syphilis was another very common illness, especially virulent in the 16th century.

The barber was the crew member who normally knew most about medicine. The greatest part of his work consisted in extracting objects, healing, cauterizing and stitching or amputating members. Treatment consisted of bleeding, vegetable medicines,... and his equipment was a mortar, spices, a cutter, medicinal herbs and strong alcohol.

They also slept on the deck, each in their own space. Only the captain had his own cabin, and even then only during the last centuries of privateering. Moreover there were no beds, only hammocks.

There were also night watches prior to which prayers would be said. Every following half-hour a ritual song was sung and each hour the helmsman and watch were changed.

The lack of hygiene, crowding on the deck and monotonous food were an excellent hatching ground for illness. Bad nutrition meant that the seamen had hardly any resistance to illness, and the danger of death through an epidemy on the ship was rife. The most common, illness was scurvy, still to be discovered, which was caused by the lack of vitamins. Only the officers had their own personal provisions (figs, sultanas, marmelade, grapes,...) with certain amounts of the necessary vitamins. Syphilis was another very common illness, especially virulent in the 16th century.

The barber was the crew member who normally knew most about medicine. The greatest part of his work consisted in extracting objects, healing, cauterizing and stitching or amputating members. Treatment consisted of bleeding, vegetable medicines,... and his equipment was a mortar, spices, a cutter, medicinal herbs and strong alcohol.

Discipline and prisoners

Sailors on Basque corsair ships could never be condemned to death no matter how serious their crime. So, free from the fear of hard, or extreme punishment, the crew was often wildly undisciplined. However, punishment did exist, such as keelhauling, which was often equivalent to the death sentence. The Basque-French had comparatively harder customs and punishments, with corporal punishment and initiation customs –such as that of tying the newly arrived to the mast and striking them- which survived in spite of being forbidden by the authorities. Murderers had the body of their victims tied to them and were thrown into the sea.Prisoners were treated kindly, when they were European. Those who hadn’t put up much of a fight were set free with supplies, but those who had put up more of a struggle had their belongings taken from them. Punishment was given to those who had tried to blow up their own ship during the fight and meant the hangman’s rope, although this was later replaced by whipping.

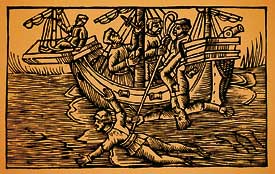

53. Engraving representing a sailor being thrown into the water several times from the stern platform, another being keelhauled and a third whose hand has been nailed to the mast with a knife.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia