Artistic expressions

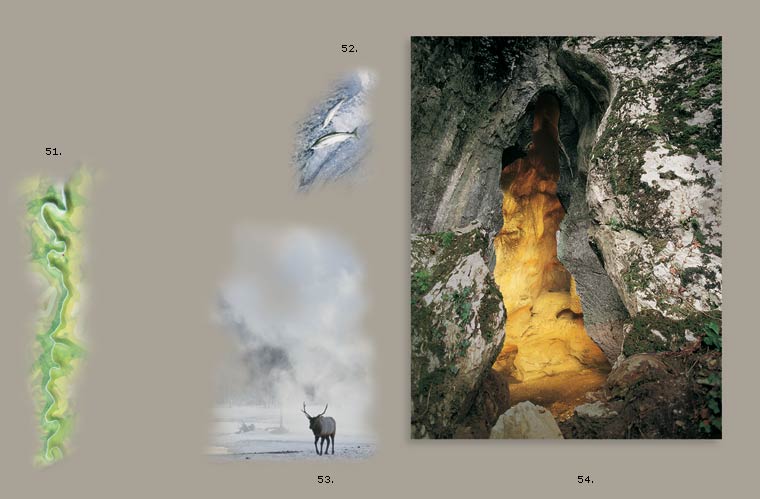

Fifteen thousand years ago, when the European mainland was enduring the rigours of the last great Ice Age, the lowlying valley of the River Deba was inhabited by groups of CroMagnon men. Here, they lived in many of the cavities in the limestone rock, where they took advantage of the low altitude and more benign climate of these areas.

At the time the numerous rocky crags of the area were inhabited by wild goats, while deer and reindeer roamed the lower zones and the entire region abounded in ptarmigans. At the bottom of the narrow valley, the river wound its way towards the coast (ten kilometres further away than it is now) between alder and other riverside species. Due to the low temperatures, the region was not covered in dense vegetation, and only a few conifers mostly pines and junipers and occasional de ciduous trees, such as oaks, birches and willows, grew in more sheltered spots.

Against this backdrop, several caves in the valley were occupied by human groups. Today we know them as Urtiaga, Ermittia, Langatxo, Iruroin and Praileaitz. Others, somewhat further away, such as the Ekain Cave in the adjoining valley of the Urola, were also inhabited for long periods. However, the people did not only live in caves and natural shelters; during the same period, they also built cabins, with roofs of branches and hides, heated by small fires. Around these they would meet to exchange their individual and collective experiences and convey beliefs about different natural phenomena as well as recounting tales of their hunting trips.

gipuzkoakultura.net

gipuzkoakultura.net

sábado 7 marzo 2026

Bertan > The Magdalenian pendants of the Praileaitz I cave(Deba) > Versión en Inglés: The cave at Praileaitz I (Deba)

- 1- Praileaitz I

- 2- The natural setting

- 3- Human beings during the upper Palaeolithic

- 4- Artistic expressions

- 5- Artistic expressions

51. Meanders in the River Deba. 52. Salmon. 53. Red deer. 54. Entrance to the Praileaitz I cave (Deba).

Each of these human establishments fulfilled a complementary function: some were more or less stable dwelling places, others were occupied for shorter periods or on rarer occasions when they were needed for exploiting specific local resources. Some were used as temporary settlements for specialised hunting or for gathering plants (fruits, tubers and leaves, etc.); others served as suitable sites for fishing or gathering molluscs; and some were used for obtaining raw materials and preparing utensils. In all of them, the people would carry out a range of tasks, making tools, eating part of their catch, and after nightfall, seeking warmth around the fire.

But of all those twinkling points of welcoming light which would have been visible throughout the valley on those cold Magdalenian nights, there is one which is of particular interest to us. By the gleam from the fire, one would have been able to make out a sinuous, suggestively shaped entrance in the light coloured limestone; an opening, in deed, that was reminiscent of the female sexual organ.

The Praileaitz I cave stands fifty metres up in the steep right hand bank of the Deba. It seems to hang over the gentle meanders of the river, its triangular NW facing entrance rising to a maximum height of six metres, two and half metres wide at its base.

But of all those twinkling points of welcoming light which would have been visible throughout the valley on those cold Magdalenian nights, there is one which is of particular interest to us. By the gleam from the fire, one would have been able to make out a sinuous, suggestively shaped entrance in the light coloured limestone; an opening, in deed, that was reminiscent of the female sexual organ.

The Praileaitz I cave stands fifty metres up in the steep right hand bank of the Deba. It seems to hang over the gentle meanders of the river, its triangular NW facing entrance rising to a maximum height of six metres, two and half metres wide at its base.

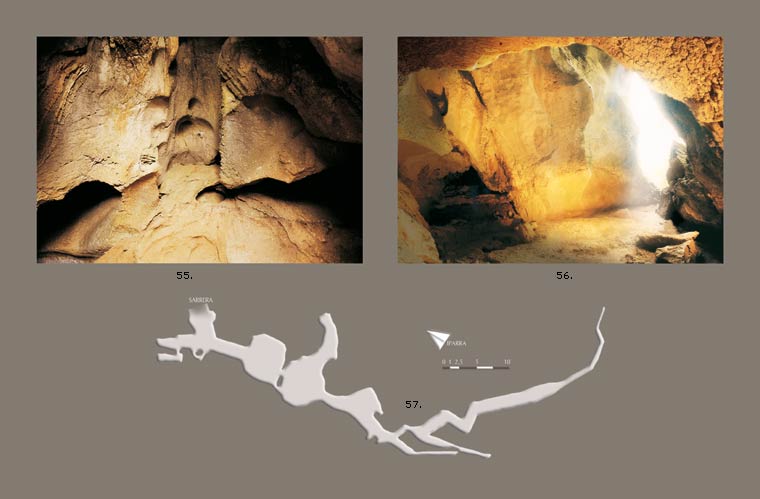

55. Formations in the vestibule at Praileaitz I. 56. Entrance and vestibule of the cave. 57. Plan of the Praileaitz I cave. © Xabi Otero

Inside, a conical vestibule, around thirty four square metres in area and somewhat over ten metres in height, is illuminated by the light from outside. Over the passing millennia the flowing water has carved twisting reliefs in its walls and ceilings.

Beyond it, a narrow passageway, scarcely a metre high, runs southward. Following this passage, we make or way through the gloom into a snug circular room with gentle walls, about seven metres in diameter, surmounted by a vaulted ceiling no more than two metres high in the central area.

Standing on the clean yellow clay in this dimly lit space, we can see the bright outdoor light silhouetting the entranceway, creating fanciful reliefs in the walls of the vestibule.

Further in, another room, also circular, disappears into the darkness. It is now covered by a thick stalagmitic layer. Behind it, narrow galleries push onward into the mountain.

While groups of hunter gatherers occupied the neighbouring caves, carving stones, working bones and feeding off wild goat, venison, fruits and roots, it is likely this space was occupied by some important figure invested with special qualities that were acknowledged by his or her contemporaries. He or she fitted out the floor of the vestibule with small, perfectly fitting limestone rocks, dug a hearth into the clay, and beside it placed a large block with a concave surface to use as a seat, braced with another large stone wedged underneath to provide greater stability. Meat for eating was stored a short distance away. Some bones, stripped of meat, were thrown on the fire.

Barely a handful of tools, flint chips and some bones have been found on the paved floor that made the dwelling more comfortable. It is a far cry from the great wealth of utensils, remnants of carving work and shards found in the neighbouring caves of Ermittia and Urtiaga.

On the ground close to the entrance to the gallery leading to the inner rooms, a few ochre pencils with clear signs of having been used were found lying among the small stones.

Standing out amidst this unusual paucity of materials and waste matter are several groups of pendants, scattered in the vestibule and in a small space behind the seat and next to the gallery that leads to the darker and deeper areas.

The inner room is even more unusual almost magical.

It is as if the circular space had been swept clean to remove any bones and utensils, and everything apart from the clay on the floor and a few stones had vanished.

Beyond it, a narrow passageway, scarcely a metre high, runs southward. Following this passage, we make or way through the gloom into a snug circular room with gentle walls, about seven metres in diameter, surmounted by a vaulted ceiling no more than two metres high in the central area.

Standing on the clean yellow clay in this dimly lit space, we can see the bright outdoor light silhouetting the entranceway, creating fanciful reliefs in the walls of the vestibule.

Further in, another room, also circular, disappears into the darkness. It is now covered by a thick stalagmitic layer. Behind it, narrow galleries push onward into the mountain.

While groups of hunter gatherers occupied the neighbouring caves, carving stones, working bones and feeding off wild goat, venison, fruits and roots, it is likely this space was occupied by some important figure invested with special qualities that were acknowledged by his or her contemporaries. He or she fitted out the floor of the vestibule with small, perfectly fitting limestone rocks, dug a hearth into the clay, and beside it placed a large block with a concave surface to use as a seat, braced with another large stone wedged underneath to provide greater stability. Meat for eating was stored a short distance away. Some bones, stripped of meat, were thrown on the fire.

Barely a handful of tools, flint chips and some bones have been found on the paved floor that made the dwelling more comfortable. It is a far cry from the great wealth of utensils, remnants of carving work and shards found in the neighbouring caves of Ermittia and Urtiaga.

On the ground close to the entrance to the gallery leading to the inner rooms, a few ochre pencils with clear signs of having been used were found lying among the small stones.

Standing out amidst this unusual paucity of materials and waste matter are several groups of pendants, scattered in the vestibule and in a small space behind the seat and next to the gallery that leads to the darker and deeper areas.

The inner room is even more unusual almost magical.

It is as if the circular space had been swept clean to remove any bones and utensils, and everything apart from the clay on the floor and a few stones had vanished.

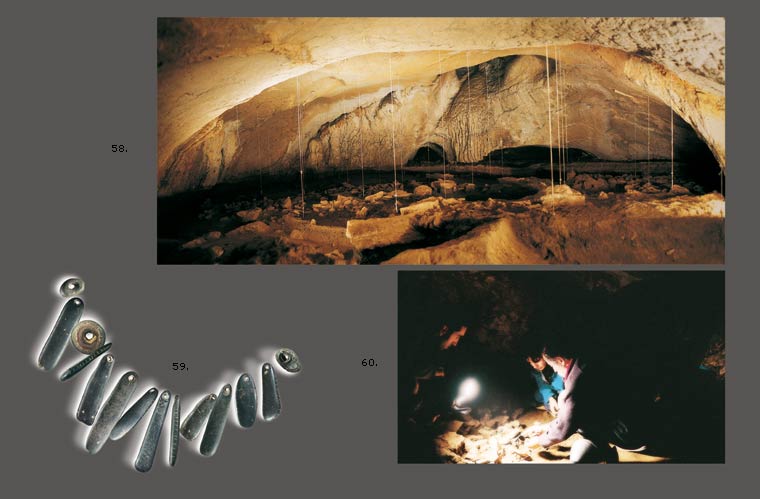

58. Overview of the inner room where two of the necklaces and a number of broken pieces have been discovered. In the foreground, the vaulted tunnel leading to the room. 59. Necklace from Praileaitz I. 60. The fourteen constituent parts of the necklace gradually emerge. © Jesús Alonso

In all, there are twenty three pendants grouped in five sets, and another six which are broken close to the perforation hole. Three of them are located on one side of the inner room.

Except for three decorated wild goat incisors, one bearing marks of red ochre, all the pieces are made of black stone. Many are elongated. They were probably selectively gathered in the nearby River Deba, perhaps not only for their aesthetic appeal but also because of the symbolism their shapes and outlines suggested.

They may also have been chosen for their gentle texture, so typical of rounded pebbles, and the shine they took on when dampened by water or sweat.

The gatherer decorated most of the stones, insistently carving transverse incisions on several surfaces and edges. As they gradually emerge from the clay, however, we can see that each one bears different rhythmic patterns, groups of incisions and gaps. We do not know what they were used for or what they stood for. Were they simply decorative? Might they have had some ostentatious or hierarchical value? Or are they perhaps the only remaining testimonies of some ritual activity?

Except for three decorated wild goat incisors, one bearing marks of red ochre, all the pieces are made of black stone. Many are elongated. They were probably selectively gathered in the nearby River Deba, perhaps not only for their aesthetic appeal but also because of the symbolism their shapes and outlines suggested.

They may also have been chosen for their gentle texture, so typical of rounded pebbles, and the shine they took on when dampened by water or sweat.

The gatherer decorated most of the stones, insistently carving transverse incisions on several surfaces and edges. As they gradually emerge from the clay, however, we can see that each one bears different rhythmic patterns, groups of incisions and gaps. We do not know what they were used for or what they stood for. Were they simply decorative? Might they have had some ostentatious or hierarchical value? Or are they perhaps the only remaining testimonies of some ritual activity?