gipuzkoakultura.net

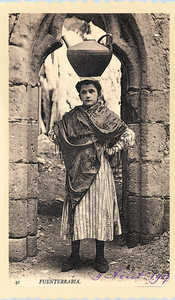

This type of pitcher (known as a pedarra, pegarra, kantarue, etc.) was used in much of Gipuzkoa to transport water. When Humboldt was travelling through St Jean de Luz in 1801 he was fascinated by this vessel, which he described as being shaped like a teapot.

It does not appear to have made by Gipuzkoan potters, but was instead imported from craftsmen in the French Basque Country, such as the Cazaux family in Biarritz (Lapurdi) Jean Oyhamburu and Simon Eyheraberri in St. Jean le Vieux (Donazaharre) in Lower Navarre and Gathulu Urdiñarbe in Zuberoa. They might also have come from the potteries of Doneztebe (Navarre); we do know, for example, that the Remón family manufactured them in Galzaburu.

These pitchers had no form of waterproofing, unlike those made in potteries in Alava and Bizkaia, which were enamelled in white whenever possible. They were then glazed, although in some cases an engobe underglaze was added first.

The area in which this type of pitcher was used has not been sufficiently well studied and given the apparent antiquity of the piece, it seems well worth the research.

R. Coquerel found one dating from the Carolingian era at Saint Lézer. Speaking of the Ordizan pitcher, he says that they were made without a wheel or latterly with a very rudimentary one:

Given their shape and texture, the vessels from Ordizan are entirely comparable to those of the Carolingian era. At Saint Lézer we found a large pitcher dating from this period and though it is somewhat more elegant in form, it bears more than a passing resemblance to the pitchers of Ordizia. This technique, dating from the high Middle Ages was preserved until the end of the nineteenth century.

In the 1970s, in the interesting Bearne museum in Pau, I saw a pitcher dating from the third century, whose shape suggested that it was a precursor of the Pyrenean pitcher. Next to the handle, it bears the potter's mark: three incisions with another one crossing them diagonally. This custom of putting the potters' mark on the vessels in this part of Bearne survived almost to the present day.

An engraving published in "Theatrum Orbis Terrarum" by Abraham Ortelius of Antwerp in 1603, bears the legend Donsellas Biscainas and Gasconas...

[Biscayan (Basque) and Gascon maids]. It shows one of girls carrying a pitcher, similar to the Pyrenean one, on her head. The handles of the jug, however, can be folded down by means of pivots on the ends. The vessel appears to be made of metal. There are many postcards and engravings illustrating the use of this vessel in these areas. One postcard from Biarritz shows a pitcher with a horizontal handle. Julio Caro Baroja, in his work "De la vida rural vasca (Bera de Bidasoa)", says:

For carrying water, as well as a subilla, a clay pitcher or pedarra is also used, which is generally imported from France. Like the Spanish word herrada, the name pedarra most likely comes from the Latín "ferrata". It is well known that the Basques tend to turn the F into a P.

José Miguel de Barandiaran, in his "Bosquejo Etnográfico de Sara V" (published in the Anuario de Eusko Folklore, Volume XXI, (1965-66), page 110), says: Pedar: the jug is called pedar, pear or pegar. It is a clay vessel measuring 25 cm across at the widest point. The mouth is 8 cm in diameter and the base 16 cm. It has a handle (gider) on one side and a spout (tutu) on the other.

These, then, are the different names by which this pitcher is known in the Basque Country: kantarue , in Bizkaia; pedarra , in Doneztebe (San Esteban) and Bera de Bidasoa; pegas , in Biarritz, and pedarra , pegarra or pearra in Sara. These last names are very frequent in Northern Navarre, the French Basque Country and adjoining areas, such as the southern part of Les Landes, according to Jean Seguy's Atlas Lingüistique de la Gascogne . In the eastern part of the French Basque Country it is known as ourse (likewise in Poyastruc and Lahitte de Toupière, important pottery centres, where the vessels were thrown without turning on a wheel).

Jean Robert, curator of the Pyrenean Museum in Lourdes, says that this pitcher was also known by the Gascon word terras , and this is confirmed in Jean Seguy's Linguistic Atlas. Further east, according to Seguy, it was called a durno . In Les Landes, further north than the area where the term poega is used, it was known as a banoe . According to R. Coquerel, in Lahitte de Toupière, where the last vessels were fired in 1926 (Bulletín de la Société Ramond Bagnères de Bigorre, 1969), a pitcher somewhat smaller than the ourse was also produced, which might be included in the same family. This was called a péaderates , and had the handle on the mouth. The pitchers used in Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and part of Alava were generally tin-enamelled inside and out. In some cases, they were only half-glazed on the outside. As was the case with other vessels, when tin became scarce and the price rose to prohibitive levels, they began to glaze them, leaving the colour of the clay visible.

However in northern Navarre, in the French Basque Country, and in the other areas mentioned, the pitcher was entirely unglazed. Only in the Ariège valley and in Lahitte de Toupière have we seen decorations, consisting of a few simple strokes of engobe.

In some places it was the custom during the village fiestas, to hold races in which the competitors had to run with pitchers on their heads. There are pictures of this practise from Zornotza and Orereta. R. Coquerel speaks of this custom in Poyastruc. Juan Carlos Epalza tells me that this race was also held in Ibarra (Orozko).