gipuzkoakultura.net

The Romans were in general tolerant of the religious practices of subject or colonised peoples. The only exceptions were their problems with the Jews and Druids, both of which undoubtedly had a political background, and later with the Christians, who were considered to be subversive of the established order. Only on one issue was compliance deemed compulsory - that of the cult of the emperor. Once this had been accepted there was room for the rites and traditions of other cultures, some of which made their way into the Roman pantheon. Many local gods could be identified with the figures of Mars or Jupiter, and could thus be associated with them in worship: thus we find Mars- Sutugi in Comminges and Jupiter-Besirisse in Cadéac. Some deities travelled thousands of miles, as was the case of Mithras whose cult was spread by soldiers from its birthplace in the Middle East to the furthest corners of the empire, to become a socially important movement. Other gods, like the Celtic Deba and Arno, remained close to home. In practice the Romans had a wide-ranging pantheon with all kinds of major and minor gods covering practically the whole gamut of human activity. There was a god of war and of hunting, there were gods of rivers and fountains, gods for the protection of roads and navigation, a god of love, family gods who were worshipped at home, and so on. Daily life involved a constant relationship with divinities, and superstition and fetishism were endemic.

This is the context to which the four idols found at Higer (Asturiaga-Hondarribia) belong. They appeared in the sand on the sea-bed alongside other articles indicating that they may have been part of a ritual hoard. They were accompanied by a jar of relatively sophisticated design, trays, and part of a lock, suggesting that all these items were originally held in a single container, perhaps a chest, and that they date from the middle of the second century. The idols, in the form of lamps, represent the goddess Minerva with a helmet and a breastplate on which appears the symbol of the Gorgon; the god Mars, bearded, with a breastplate and helmet; Helios, the sun-god, with his crown of rays; and the goddess Isis with the symbol of the moon above her head.

The sun-god Helios also features on an oil-lamp recovered from the Roman mine of Arditurri III in Irun. The association between the symbol and the function of the lamp seems clear, especially if we bear in mind how dark the mines must have been. A figure of Minerva is also said to have been found in Renteria, but it has since disappeared, and there is no evidence at this time to attest its origin, or even that it comes from Gipuzkoa.

Other representations of gods from the 'official' pantheon include an image of the goddess Roma on the stone of a ring found during excavation of the Roman port at Tadeo Murgia St in Irun. The cameo or engraving is oval in shape and carved on a semi-precious stone. It is 13 millimetres in length and represents the divinity seated on her throne with all her symbols (helmet, shield, spear and victory scroll stretched over the palm of her left hand). The miniature is of very high quality, with very detailed carving showing the features and folds of the dress, the facial features of the figures and the details of the associated furniture in bold perspective.

We have already mentioned the Celtic deities of Deba and Arno as examples of the way native gods survived despite the spread of official cults. They may well have lived on in local place names too: it is quite possible that Arno Mountain and the nearby River Deba bear some relation to local cults. The cave of Santaili in Araotz, appears to derive not from St Elijah (Elias), but rather from St Ylia or Julia. She was in turn linked to the goddess Ivulvia, named on an inscription in Forua, in the Gernika estuary, who was associated with a cult of water worship. The small stone slab in Oltza at the foot of Aizkorri was probably used as an altar on ceremonial occasions.

Another well-documented feature of Roman spirituality were the funerary cults. The finest representation in this area is the necropolis of Santa Elena (St Helen) in Irun, but two epigraphs have also been found, one in Andrearriaga, described above, and the other at the foot of the altar of the chapel of St Peter in Zegama.

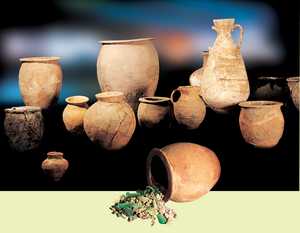

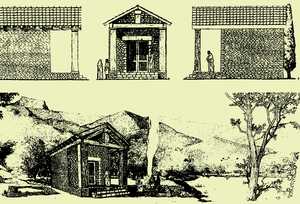

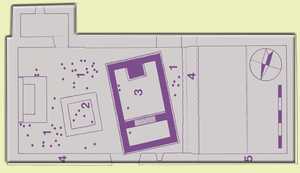

Excavations inside the chapel in 1971 revealed part of the cemetery of Oiasso. The find consisted of 106 urns containing the ashes of the deceased, most of whom were interred without any identifying features. Together with the urns, which also contained funerary hoards made up of objects like glass phials, hairpins, weapons and brooches, two stone constructions were discovered. One has a three-metre square base and has been identified as a cella memoriae or grave of importance. It contained the only glass urn found in the vicinity, indicating the high social rank of the deceased. The other has a rectangular base five metres wide by seven and a half metres long and is a replica of the simple in antis temples. It includes a small porch adjoining the cella or principal chamber, as well as a roof of tegulae or rooftiles, whose remains were discovered amongst the rubble resulting from the collapse of the building after it fell into disuse in the fourth century.

Cremation was not exclusive to the Romans, nor was it their only funerary tradition (they also buried their dead), but it was the general practice among Iron Age peoples. As Eastern beliefs were introduced and Christianity spread, however, it became less common and in time was completely replaced by burial.

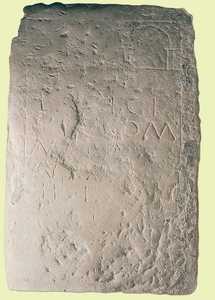

The inscription is engraved on a slab of sandstone placed at the foot of the altar of the chapel. There are five lines of text giving the name of the deceased (LANICIVS, LATICIVS, LARICIVS or possibly L.ANNICIVS), his particulars and his age at death (forty), finishing in the funerary formula H(ic) e(st) or H(ic) i(acet). Above the text three arches are traced, symbolically depicting the gates of Hades or the House of the Dead. The stone dates from the end of the first or beginning of the second century A.D. and has been associated with Alavese inscriptions.

During the fourth century Christianity ceased to be a proscribed and persecuted movement and became the religion of the emperors and later, the official religion of the empire itself. This new state of affairs brought about myriad changes in everyday life, as we can see from the items discovered from the period. A coin minted by the usurper Magnentius (350 - 355), found in Behobia, bears in the reverse the monogram of Christ and the Greek letters alpha and omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet. These two letters were employed in the cryptic language of the early Christians to refer to the divinity of Christ, who was considered to be the beginning and end of all things. On crockery too, the hitherto usual motifs of hunting scenes, pagan rituals and so on, were discarded in favour of Christian symbols such as crosses, monograms of Christ, palm-branches and others. Several examples of this pottery, derived from Early Christian sigillata

, have been found in the Iruaxpe III cave in Aretxabaleta, which from their context appear to date from the fifth century. Others found at the Higer headland date from about the same time. Nonetheless, not all of Gipuzkoa abandoned paganism in favour of Christianity. In 1993 a number of cremation urns from around the eighth century were discovered inside the chapel of San Martin de Iraurgi in Azkoitia, clear evidence of the continuance of the old pagan funerary traditions.