THE 17th CENTURY

The golden century of Basque privateering

The 17th century was a golden century for Basque corsairs. Privateering took on such importance that the Royal Decree of 1621 set down Royal Laws of Privateering –as General Laws- which stated the rules to be followed by those carrying out this profession.In this century the province of Gipuzkoa was the corsair area of the Basque Country par excellence and, as Otero Lana says, of the peninsula.

Bilbao started controlling trade, and the Bilbao Consulate was created, meaninig that all Basque trade was centred in this town. The economic dynamic of Bilbao put Donostia-San Sebastian out of places as a commercial port and the latter, in order to revitalize its own trade, didn’t manage to create its own Consulate until 1682. The reduction in trade and the need for resources made Donostia-San Sebastian into the main privateering port of the Peninsula. This situation brought two groups into confrontation; the owners of ships for privateering and traders, who were against privateering since it frightened off merchants. Between 1622 and 1697, according to Enrique Otero, there were forty-one licenced shipowners in our city and two-hundred-and-seventy-one privateering ships. Some of these were foreign, especially Basque-French, Bretons and Irish.

Hondarribia was the second peninsular port, followed by Pasaia and, far behind the others, Orio, Zarauz and Getaria.

This expansion of privateering meant a logical increase in their areas of action. The traditional areas, such as the Basque coast and the Indies, were still considered as such, while the waters of northern Europe –France, England, the Netherlands and Ireland- spread further north, and others, such as the waters of Newfoundland, were abandoned.

77. Seal of a basque port. 17th century.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

78. Shield of the Consulate of Donostia-San Sebastian.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Newfoundland and the seas of the north

We said previously that, by the end of the 16th century, fishing in Newfoundland had started declining due to political reasons. In addition to this was the exhaustion of whale fishing in the great bay, which became evident during the 17th century due, according to some, to the decrease in their number, to their fleeing from being hunted by man or to emigration because of a change in water temperature.So, the Basques gradually abandoned these lands, although certain documents state that they were still present in Newfoundland during the first decade and even up to the middle of the century we are now dealing with. There were still whales on the Basque coasts, although these were also in decline from the 14th century onwards.

However, this didn’t mean a reduction in whale hunts, but rather the opposite, through a movement towards the seas of the north. In 1612, Juan de Herauso, from Donostia-San Sebastian, left for "Groillandt, which is further north than Norway and could provide more abundant fishing". The voyage was a succes and, on their return, they convinced another twelve ships to leave for the same point a year later. On reaching the said coast, two English war galleons robbed them one after the other aince, according to the people from San Sebastian, the English arrived and made them fish for them, all on the strength of a letter of marque from the King of England.

Years later the Basques were sought out by the English for hunting whales in the Artic, since they were "skilled users of the harpoon". The English were in charge of the ovens and casks. Twenty-four Basques embarked on English ships under the orders of Baffin, en route for Spitzbergen. From then on, there are several testimonies of the death of Basque seamen at the North pole, to the north of Iceland, and in the Norwegian Sea.

79. Gipuzkoan coast.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

80. Hondarribia was the second peninsular port in importance with respect to corsairing during the 17th century.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

The Basque coasts

The foreign danger

The Basques were not only outstanding corsairs on our coasts, but also had to suffer its consequences themselves.Dutch corsairs attacked the Basque coast, sometimes even using some parts of it as their own base, and as lookout posts.

The fear of foreign invasion was ever present, as was the case in Donostia-San Sebastian, a fear which increased in 1626 due to the threat of attack by the English. For this reason, an order was given to close off the Urumea river, at the height of Saint Catherine bridge, with a chain and wooden breakwater from the Land Port to the sandbank. However, things did not turn out as planned.

Most active in this sense were the pirates from La Rochelle, who had already attacked the Gipuzkoans by the end of the 16th century.

In 1621, the Gipuzkoans wrote to representatives from Saint Jean de Luz, and the following year to those from Ciboure, asking them for arms and protection against the pirates from La Rochelle, who attacked the Basque coasts almost every winter where they had more than enough to keep them busy. To quell the hard attacks by these pirates, chastising expeditions left for the port of La Rochelle led by corsairs from Saint Jean de Luz, who were backed by Royal permission.

However, our seamen were not always prejudiced since, as Camino said, corsairs from Donostia-San Sebastian captured one-hundred-and-twenty ships carrying merchandise during these years from the pirates from La Rochelle and the Netherlands.

81. Engraving by De Bry, from 1601, representing a ship surrounded by ice.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

82. Map of Spitzbergen. Basque sailors were hired by the English to hunt whales in the Artic.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

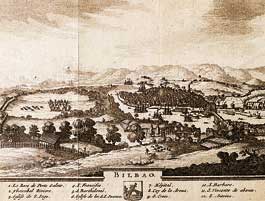

Gipuzkoans in Bilbao

In order to take prisoners, Gipuzkoan and Biscayan corsairs would go to the port of Bilbao, which was usually full of ships due to the moment of prosperity being enjoyed by this town, where they would wait in the vicinity of the Estuary for good Dutch and English prey, which they would then board.Outstanding was the captain from Donostia-San Sebastian, Agustín de Arizabalo who situated himself at the mouth of Bilbao port and who, in 1658, caught every merchant ship coming from the north of Europe, France, Netherlands and Portugal.

This Gipuzkoan attitude of attacking foreign ships in the Bilbao Estuary, was responded to by complaints, timid at first and then stronger from the Netherlands, which were made to the Consulate in Bilbao. And they were right, since the Gipuzkoans were acting like true pirates, entering into the Biscayan ports as if they were in their own home, to plunder from foreigners with the greatest of impunity. .

83. Engraving of La Rochelle port.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

84. Map of the port of Donostia-San Sebastian. In the left is Santa Catalina Bridge.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Attempts at defence

Moreover, as from 1688, light French frigates, whalers which had been equipped with artillery for the occasion, became the terror of the Atlantic coasts. The time when there were most of these ships was when the fight by the French King Louis XIV worsened against the European allies of the Augsburg league, amongst which was Spain. Some of these frigates dedicated themselves to privateering on the Basque coast, so the Consulate of Bilbao and traders of Donostia-San Sebastian took action.In 1691, the Consulate of Bilbao chartered two frigates to keep watch on the area, who defeated a fleet of French corsairs.

In order to maintain safety on the coast, traders from Donostia-San Sebastian built a frigate in 1690, the command of which was given to Pedro de Ezábal, who lived on the sea front, and who set out to privateer with a royal letter of marque, taking several ships prisoner from amongst the French, which were swarming over our seas and terrorizing them.

85. Engraving of Bilbao. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

86. In 1690, a frigate was built for corsairing and defending the coast of Donostia-San Sebastian against attacks by the French.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Royal instructions for this frigate stated:

"The traders of this City have manufactured a warship of three hundred tons, with forty-two pieces of artillery, called "Nuestra Seńora del Rosario", to privateer and guard these coasts against invasions by the French; and, having gone out to sea for this reason, in virtue of the letter of marque issued by His Majesty, manned by people from the land, it has captured many French ships and brought them to the port of this city, from where it set forth; having fought with such courage and good fortune that it has instilled terror and chased the French away from these coasts, as they were infesting the area to such an extent that they were closing the ports, even placing themselves below the cannons of the "Mota" Fort...". It didn’t take the authorities long to realize the advantages of favouring the energies of the Basque seamen, who they started encouraging in order to gain control over them. Then peace was signed in Ryswick, in 1697, putting an end to the war between the Augsburg League and the "Sun King" (Louis IV).

"The traders of this City have manufactured a warship of three hundred tons, with forty-two pieces of artillery, called "Nuestra Seńora del Rosario", to privateer and guard these coasts against invasions by the French; and, having gone out to sea for this reason, in virtue of the letter of marque issued by His Majesty, manned by people from the land, it has captured many French ships and brought them to the port of this city, from where it set forth; having fought with such courage and good fortune that it has instilled terror and chased the French away from these coasts, as they were infesting the area to such an extent that they were closing the ports, even placing themselves below the cannons of the "Mota" Fort...". It didn’t take the authorities long to realize the advantages of favouring the energies of the Basque seamen, who they started encouraging in order to gain control over them. Then peace was signed in Ryswick, in 1697, putting an end to the war between the Augsburg League and the "Sun King" (Louis IV).

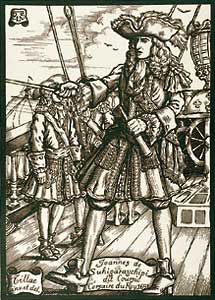

Joanes de Suhigaraychipi, "Le Coursic"

One of the French corsairs who were then attacking our coasts was Joanes de Suhigaraychipi from Bayonne, better known as "Le Coursic", (the little corsair). He was one of the King’s corsairs and won titles of nobility for his feats and services.His frigate, the "Légčre", was authorized to privateer against the Spanish and also against the Dutch. He was so successful that the governor of Bayonne himself paid half the amount towards arming his frigate, which had twenty-four cannons. The resulting operation was so fruitful that he had captured a hundred ships in less than six years. With the support of other people from his family, his frigate, which would leave from the port of Sokoa, didn’t take long to become the terror of the English and the Dutch.

One of his most famous feats took place in 1692, precisely in our waters, since it could be seen from the San Sebastian beach. It started at the port of San Antonio, in Biscay, where he saw two Dutch ships coming towards our capital, catching up with them in two days. He caught up with the first, weighing five-hundred tons, with thirty-six cannons and a hundred seamen, which he attacked with a volley of fire. He came alongside it twice, in spite of the difference in size and, damaged, had to retire from enemy fire, which didn’t stop him from continuing to harangue the Basque-French. The fight lasted for five hours and was so fierce that there were only eighteen members of the whole Dutch crew left in the end. The second Dutch ship was also sunk. Instead of tragedy, only five Basque sailors died.

87. The horizon has always been a challenge to seamen. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

88. Joanes de Suhigaraychipi, "Le Coursic", the famous corsair from Bayonne. (Drawing by P. Tillac).

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

A few days later, "le Coursic" returned to sea. No sooner had he crossed the outlet of the Adour, than he was attacked by an English corvette equipped with a-hundred-and-twenty men and sixty-four cannons. The Bayonnese attacked it quickly that it could barely put up resistance. The result of the fight, which began at eight o’clock in the morning and ended at three in the afternoon, was victory for the "Légčre", which took the English boat captive. That victory, celebrated by the public crowded along the banks of the canal, was talked about so much that he ended up giving classes on privateering for equipping more corsairs, all under his command, in preparation of a new Spanish fleet which was getting ready to set sail.

He later captured two Dutch ships in the Gulf of Biscay.

Outside our waters, we mustn’t forget to mention the expedition which he made to Spitzbergen, in the north of Europe, against the Dutch, from which he returned with a load of whales.

In six years he alone caught a hundred merchant sailing ships and, in eight months, with the help of the king’s frigates, a hundred-and-twenty-five. He filled the port of Saint Juan de Luz so full of his spoils, that the governor of Bayonne wrote to Louis XIV: "You could walk from the house in which Your Majesty is lodged, to Ciboure, on a bridge made from captured ships tied one to the other". This prodigious audacity was linked to the loyalty of a gentleman. Anyone who didn’t keep their word or who was guilty of betrayal, was punished relentlessly.

After several years he started dedicating himself to protecting the Basque-French and Bretons from the English during their return voyage from Newfoundland. He died in these lands in 1694, where there is a headstone stating "Captain of the king’s frigate", the same person who gave him the authorization to strip one hundred merchants of their loads.

He later captured two Dutch ships in the Gulf of Biscay.

Outside our waters, we mustn’t forget to mention the expedition which he made to Spitzbergen, in the north of Europe, against the Dutch, from which he returned with a load of whales.

In six years he alone caught a hundred merchant sailing ships and, in eight months, with the help of the king’s frigates, a hundred-and-twenty-five. He filled the port of Saint Juan de Luz so full of his spoils, that the governor of Bayonne wrote to Louis XIV: "You could walk from the house in which Your Majesty is lodged, to Ciboure, on a bridge made from captured ships tied one to the other". This prodigious audacity was linked to the loyalty of a gentleman. Anyone who didn’t keep their word or who was guilty of betrayal, was punished relentlessly.

After several years he started dedicating himself to protecting the Basque-French and Bretons from the English during their return voyage from Newfoundland. He died in these lands in 1694, where there is a headstone stating "Captain of the king’s frigate", the same person who gave him the authorization to strip one hundred merchants of their loads.

89. View of Ciboure from Saint Jean de Luz.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

90. The house of "Le Coursic" can still be seen in Bayonne, in the street of the same name.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Corsairs in Europe

An unlucky man from Renteria

We have already seen how, in addition to the Basque coasts, the other great stage where the Basque corsairs would go to carry out their acts, was the north of Europe.Around the years 1626 and 1627, six ships and three tenders from Donostia-San Sebastian took part in a pirate operation around Ireland and Scotland, of which we only know, thanks to J. César Santoyo, owner of the "San Jorge", commanded by Miguel de Noblecía from Renteria, that the ships acted alone. The first year of the expedition brought no results, because the people from Donostia-San Sebastian in the Irish port of Berchavan who virtually had their prey in their hands, were fightened off by the Irish and came home. The next year, the "San Jorge" set sail once again from the beach of Donostia-San Sebastian and reached the same port as the previous year, where they took on "legal" provisions. They then set off for the west coast of Ireland, hoping to find a catch, but, as they didn’t find anything, they had to resort to finding one on land. They proposed that three Irish traders come on board, one of whom returned to land to pay the ransom for the other two and get supplies for the pirates. But once this had been done, an English warship cut off their retreat and they ended up in prison.

91. Juan Larando’s inn.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

92. Different kinds of swords from the 16th and 17th centuries.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Juana Larando: a corsair widow from Donostia-San Sebastian

As we have already seen, the outstanding role which Donostia-San Sebastian had taken on as a corsair port attracted professional shipowners from all over, as well as sailors from the neighbouring areas to the north of the peninsula and further abroad, people who stayed in the guest houses, between expedition and expedition.In 1630, Juana Larando, a widow from Donostia-San Sebastian, had a guest house where she would give lodgings to some eighteen adventurers from greatly differing origins, providing them "with everything on credit, until they would come back with a capture and get paid for what it was worth", as is documented in the Tolosa "Corregimiento" Archive.

She invested her profits in a tender or small boat with two partners, one from Orio and another from Donostia-San Sebastian, which they christened with the name of "San Juan". The tender, captained by Juan de Achániz, worked along the French coast and in the "English channel".

During one of its voyages the tender managed to make a catch of twelve thousands ducats. On the return voyage there was mutiny on board; the "San Juan" was wrecked and abandoned and they captured a better, Dutch boat, called the "San Pedro". With this they reached Zumaya, where they sold it for eleven-thousand-one-hundred-and-fifty-five “reales”.

The sharing out of the money caused a great uproar. Even the Orio village priest had a share –as he had been asked to say mass for the successful outcome of the "San Juan" venture- as did the interpreter of the resulting court case, then there was the food given to the imprisoned Flemish –before they were returned without a ship- and the price of the sloop in which they sent them back to their country. The result of the division was thus: they gave the widow Juana de Larando three-thousand-six-hundred-and-nine "reales"; Captain Echániz, six-hundred-and-seventy-seven; the interpreter, one hundred "reales", while each corsair only got eighty six "reales", a meager amount for such an exceptional catch.

Royal support

However, it was not all a question of acting on their own behalf and taking risks. Royal backing was also given to privateering during this century, support by the Crown to the Basque corsairs or work to order.In 1633 the King ordered that a fleet of ships be formed to privateer against the rebels and enemies of the Royal Crown, in which everyone offering to work would take part as an officer or crewman.

It is testimonies of this type which help us to deduce that not all corsairs came from the coast. It is quite difficult to find mentions in books about corsairs coming from areas in the interior of the province. However, there is evidence of Antonio de Aguirre, from Abaltzisketa; the men from Amezketa, Juan de Zuriarrain or Miguel de Gorostegui; or from Ataun, José de Goicoechea and from Tolosa, Ignacio de Bengoechea, amongst others.

As from 1660, corsair ships from Donostia-San Sebastian and Hondarribia established themselves in Galician ports which they used as a base for their continuous corsair voyages to England, the English Channel and Ireland, destinies more easily reached from these waters.

And so they continued, until peace was signed with France. Gipuzkoa and Labourd signed yet another agreement in 1652, as they had done in the 16th century, in which they established the rules of privateering. According to these, no ships could be taken prisoner from either of their respective ports. Apart from this, the corsairs from both sides could continue with their mischief, attacking one other freely, without this being considered as having broken the truce. The agreement was approved by the Spanish and French War Councils. Its fulfilment was ordered and confirmed in 1667, 1675 and 1694.

93. Basque coast. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

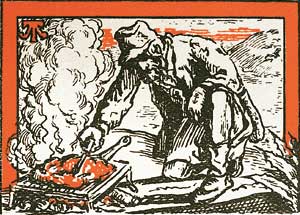

94. The term buccaneer comes from "boucan", the smoked meat made in the Antilles. (Drawing by P. Tillac).

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

"The fear of Great Britain"

Once the peace agreement had been signed with France, the Basque corsairs turned their sights towards England.According to Camino, more than ever in the decade of the 50s to the 60s "corsairs from Donostia-San Sebastian were famous for terrorizing the seas, instilling fear in all of Great Britain’s seafaring vessels". Antonio de Oquendo, for his part, assures that "the hostilities which England suffered at the hands of the frigates from Donostia-San Sebastian and Pasaia, was one of reasons which drove them to ask for peace".

To understand this fear of Donostia-San Sebastian better, we have information issued in 1682 by the Donostia-San Sebastian Consulate, which assured that... "in 1656, there were two ports in this city with fifty-six ships from both the port itself and the province, which carried out hostilities against enemies of the Crown, causing constant serious damage to English navigation and trade, obliging that Kingdom to made peace".

Fermín de Alberro was one of these corsairs. In 1684, he anchored off Wales, waited and boarded a ship from Bristol, which was going to Bilbao with lead, cloth and plans. The ship entered the Biscayan capital empty, while its load entered the quay of Donostia-San Sebastian, accompanied by the cheers of the whole neighbourhood who had come along to take part in the event.

Corsairs in the Indies

16th century style attacks were still being carried out by the English and French in the 17th century on the weak Spanish fleet, which was now suffering from other problems: the contraband carried out by the former and attacks by buccaneer pirates established in the different Caribbean ports, and mainly Tortuga Island, who, backed by the English and Dutch from these colonies, were the nightmare of all the rich emporiums in the Antilles and of the ships carrying out intercolonial traffic. The name of these buccaneers came from the word "boucan", the smoked, dried and salted meat which they produced.Spain’s answer to the problem of contraband in the Caribbean was the concession of letters of marque to corsairs who patrolled along the coast of the colony arresting suspicious foreign ships. The ships and artillery taken were passed on to the Spanish fleet for defending the colonies.

Several Basques stood out notably from amongst the corsairs and pirates in the Indies.

Tomás de Larraspuru

Tomás de Larraspuru, from Azkoitia who was in time raised to the rank of admiral, arrived to the Antilles in 1622 at the head of fourteen galleons and two tenders with an end to cleaning up the enemy islands. Based at Margarita island, he went round the whole Caribbean ridding the smaller islands of the dens belonging to English and French contraband organizations, and setting up the fleets of New Spain and Terra Firme. A year later, he arrived back to Spain with a treasure of almost thirteen million in lingots and fruit, having acquired the fame of being the best general to have governed the fleet. He died ten years later.Michel "le Basque"

After Larraspuru, the Dutch used their naval power to break Spanish supremacy in the Caribbean, leaving the Antilles at the mercy of foreign attacks.One of those who wouldn’t be put down was Michel "le Basque" from Saint Jean de Luz. This man set himself up in the second half of the 17th century on Tortuga Island, in association with another buccaneer, "el Olonés", with whom he carried out some of his attacks. First he took over a galleon in Porto Bello port, which had a splendid booty. Years later, in 1666, he decided to attack the highly active port of Maracaibo, which was defended by two-hundred-and-fifty men and fourteen cannons, pillaring it and making its population flee. He stole the ecclesiastic ornaments, with the intention of taking them to the church he intended to found on Tortuga Island. The following year, with only forty men, he attacked Maracaibo again and stole an important amount.

95. Michel le Basque.© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Years later, the governor of Cartagena wanted to clean the area of pirates, and sent a small fleet to get rid of them. But Michel "le Basque" only needed a couple of brigantines to take charge of the government ships and return them to the governor with his gratitude.

Michel "le Basque's" vessel was the frigate "la Providence" built in Saint Jean de Luz. It had sixteen cannons. It was manned, apart from Michel "le Basque" and Captain Larralde, by around forty men.

Michel "le Basque's" vessel was the frigate "la Providence" built in Saint Jean de Luz. It had sixteen cannons. It was manned, apart from Michel "le Basque" and Captain Larralde, by around forty men.

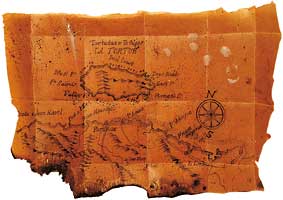

A Gipuzkoan armada bound for Tortuga Island

The problem of pirate attacks in the Indies continued without a solution for several years.According to a bundle of papers given to me by José Garmandia from the General Indies Archive, some Gipuzkoan shipowners prepared a fleet of frigates to fight against corsairs in the Indies in 1685.

This took the form of a contract with the Gipuzkoan shipowners to prepare a fleet for fighting against the English pirates who were swarming around the Indies. The Indies War Council negotiated with the Gipuzkoan shipowners to get themselves a fleet to deal with the situation. The shipowners were from Donostia-San Sebastian and Hondarribia, and they called in the Count of Canalejas as the admiral of the fleet. Three priests from San Telmo were also given a place on it since “the others didn’t understand the Spanish language”.

The construction of this fleet was carried out with great speed in the Anoeta shipyard, Donostia-San Sebastian. It comprised the flagship "Nuestra Seńora del Rosario y Animas", weighing two-hundred-and-fifty tons with thirty-five cannons, the viceadmiral’s ship, "San Nicolás de Bari", with a hundred-and-forty tons, and the tenders "San Antonio" and "Santiago". These ships were manned by a total of four-hundred-and-seventy-seven men.

Once they had reached American waters some of them fled and one of the frigates had to be sold. The fight against the English corsairs took place around Tortuga Island using a ship and a sloop.

But it would seem that the fleet didn’t meet the conditions for the fight it was supposed to win, and that the crew was not well enough prepared. We have no more information about this fleet and therefore do not know what became of it.

96. Map of Tortuga Island.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

97. Catalina de Erauso, portrait by F. Pacheco. "La monja alférez" (the ensign nun) (Donostia-San Sebastian, 1592), was one of the four survivors of the Spanish "Jesús María" flagship which was sunk by the squadron of the German corsair Georg von Spilberg, hired by the Dutch, during the battle of Cańete (1615) off the coasts of Chile.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia