THE 16th CENTURY

The 16th century of our history is dominated by the conflicts which, for political and religious reasons, brought Sapin into confrontation with France and England, causing frequent succesive periods of war and peace which Charles V and Philip II started with these two kingdoms, the stage for which was often the sea.Basque corsairs were therefore no strangers to these comings and goings, but rather played leading roles in them, sometimes thanks to royal letters of marque, and others through acting on their own behalf.

Generally, we can consider the 16th century, of which there are several testimonies, as the first to have seen the regulation of Basque corsairs.

68. Small Cannon.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

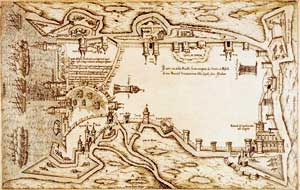

69. Map of La Rochelle port. Antonio Lafreri (1580). © Joseba Urretabizkaia

Two precedents

One of these is the exception made by a certain Antón de Garay, the first known corsair. This Biscayan from the end of the 15th century, started privateering in the Atlantic, and later continued pirating along the coasts of the New World, for which be was executed. The other, in Gipuzkoa, was Juan Martinez de Elduayen, from Donostia-San Sebastian, who did the same thing in 1480. He got hold of three pinnaces from Hondarribia which were carrying French merchandise, "on the strength of a few letters of marque and the reprisals which you say have existed since times of war". The Catholic Kings told him that this affair had been solved a long time previously. Later he attacked a vessel from Bilbao alongside Donostia-San Sebastian, with the help of his relations. This brought him another reprimand from the Kings, who took the prisoners away from him and made him sign an obligation costing a few farthings.

70. Kheyr-al-Din, better known as Barbarossa, continued the incursions of his brother, who was known by the same name. Allied to the Turkish Sultan, Suleiman, this corsair took many Gipuzkoan sailors prisoner who had to pay a ransom for their freedom.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

71. Returning to San Sebastian.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

The French enemy

Coming back to the moment in question, during the early 16th century, France was already using letters of marque as a prime weapon in its rivalry with Spain. Corsairs and pirates from La Rochelle were becoming famous amongst Basque seamen during this century, which was the prelude to the fame they would achieve in the following century. Likewise, the Captain Martín de Iribas had to attack the famous corsair from La Rochelle, Juan Florín –who had taken charge of the treasure which Hernán Cortés was sending from Mexico to Spain, making prisoners of his men whom he took to Cádiz.Basque privateering was inaugurated during this century, in 1528, when the Spanish Crown declared war against France and England and urged Gipuzkoa to arm as many of its seamen for privateering as possible.

In the Bilbao Estuary, and because of this war, French and English corsairs sometimes intercepted each other’s trade and navigation, such as in 1536, when the Consuls of Bilbao sent a letter to the magistrate in Brussels asking for artillery, as a measure of precaution against French corsairs. The corsairs from Labourd were the most important in the Basque Country, operating in all waters with or without permits, even often overlapping into the area of piracy. Famous Basque-French corsairs in this century were Duconte, Harismendi and Dolabarantz.

The Gipuzkoans were indeed armed and took so many French ships that the latter asked to go back to their earlier friendly relations, due to which a common accord was signed between the neighbouring parties in Hendaye en 1536, stipulating a pragmatic warning, according to which both sides undertook, if their Kings declared war, that the first of two to receive notice of the war order or letter of marque would rush to notify the neighbouring party so that it could take the appropriate steps.

During these wars with Spain, France allied itself with the Turkish who had a great empire at the time, were enjoying great prestige and were anxious for expansion, which took shape in the control of commercial traffic and naval supremacy in the Mediterranean. One of the Turkish leaders and pirates was Barbarossa who, thanks to their alliance with France, attacked the Spanish coasts in 1530. Gipuzkoan prisoners were taken by the Turkish, such as a sailor from Deba who had to be rescued from Barbarossa in 1533, for which his native town put up the capital.

This agreement of mutual respect signed between the two neighbours was broken years later when, in 1553, Philip II, who had still not become King, recommended that the San Sebastian shipowners set out to catch some French corsair ships which were bringing stolen goods back to France from the Antilles. However, due to this permission, the shipowners continued attacking French ships, and, on seeing this, the ships bringing supplies to Gipuzkoa stopped coming.

72. 1650 engraving of the Ciboure and Saint Jean de Luz Bay.

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

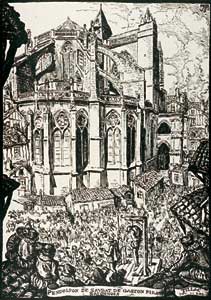

73. Execution of the pirate from Bayonne, Saubat de Gaston, next to Bayonne Cathedral. (Drawing by P. Tillac). © Joseba Urretabizkaia

Four corsairs from Donostia-San Sebastian

In 1554, four corsair captains from Donostia-San Sebastian sailed up different French canals and rivers, capturing several merchant ships and taking prisoners from enemy corsairs to the provincial prisons.Of these four corsairs, Martín de Cardel, captain and water carrier, penetrated into the Bordeaux Estuary with six ships, assaulting and stealing from the surrounding villages. He brought forty-two large French ships full of artillery and merchandise back to San Sebastian. Domingo de Albistur took over nine large French ships on their way back from Newfoundland, loaded with cod and arms, after having made the warships who were looking after them flee. In addition to this, together with Pablo de Aramburu, he took charge of forty-nine French ships loaded with cod and cannons. Of the four, it was perhaps Domingo de Iturain who was most famous. Like the above-mentioned Garay from Biscay, he started with a small ship, taking a larger and better armed ship prisoner, with which he specialized in stealing the catches taken by British fishing ships in Newfoundland.

Thus continued the attacks by Basque corsairs, until in 1559, when peace was signed with France, thereby establishing peace between corsairs.

74. Mooring ropes. © Joseba Urretabizkaia

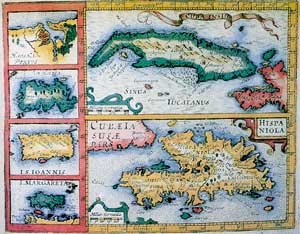

76. Cuba and La Española Islands, Havana, San Juan and Margarita. Gerardus Mercator (1610).

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

© Joseba Urretabizkaia

Piracy and Basque-French privateering

During the second half of the century, Basque-French privateering was outstanding for several reasons.In the first place, Basque-French piracy firmly and systematically established itself around this time, according to a series of strict regulations. The judges' passivity also became obvious from this moment on.

Secondly, the dirty trick which the French played on the Gipuzkoans is notorious, since both Kingdoms had signed a peace agreement.

Outstanding in this sense are the corsairs from Saint Jean de Luz and Ciboure who, around 1560, started pestering Gipuzkoan ships in the Newfoundland ports, expelling them without letting them fish; as early as 1559 a writer had said that the inhabitants of Saint Jean de Luz were always highly considered by the Kings of France, because "its inhabitants are extremely warlike, especially at sea". For example, the pirate and sea merchant from Biarritz, Saubat de Gaston, boarded some ships in 1575 and stripped them of their loads at the outlet of the Adour. Another two pirates, a certain Captain Bardin helped by a certain Motxi who, in honour of their capacity of pirates, also dedicated themselves to pillaging their King's subjects.

The impassibility of the French Admirality in the face of such facts led the French monarchy to take a position in the affair, ordering that permission only be awarded on previous payment of a deposit, and that their captures be discussed with the Admiralty.

The English enemy

But France wasn't Spain's only enemy. As we have already seen, the 1528 permit for becoming armed for privateering also concerned the English enemy, against whom war had also been declared.Against the British and in times of war, apart from the said Iturain, were Antón de Iribertegui, from Getaria, who occupied an English ship in Scotland, and Urbieta from Orio who, on arriving to London as a crew member on a merchant ship, took over an English ship, killing the crew and selling the ship, after which he had to flee from the law.

England opened a breach on another front. English piracy increased when Elizabeth I arrived to the throne, due to which Spain went to war yet again. This was the reason for maritime confrontation and English support of the pirates who attacked the fleet coming from the Indies, where the English pirates Drake and Hawkins stood out as the first to have taken piracy to America.

Gipuzkoan officers of the Crown have left us vivid records of the actions of these pirates, such as that suffered by Martín de Olazabal, commander of a large fleet which left Havana for Spain, with nine galleons full of treasure and a convoy of almost sixty ships, which was attacked by the English.

The century came to an end with the downfall of Spanish dominion at sea, due to the defeat of the Invincible Armada at the hands of the English, and the effect this had on the Basques. One of the most powerful fleets of the 16th century fell to English naval supremacy.

Even in times of difficulty for our people, our enemity with England was never forgotten. The century also came to an end with an outbreak of the plague in Gipuzkoa, which meant that ships from La Rochelle, which had set out to privateer, were able to arrive to the Gipuzkoan ports, steal and take away merchandise and even fishermen. This was enough for the authorities to request that ships from all nations be allowed to reach Gipuzkoa, except the English, in order to bring supplies: "so that all nations, except the English can freely navigate and bring sufficient provisions for the survival of the people since, as prices are getting higher every day and the fact that even with money there is nothing to buy for eating, if France stopped coming, great damage would probably be caused through widespread starvation".