gipuzkoakultura.net

The fortifications of the last third of the nineteenth century are a result of the innovations that military architecture was forced to introduce to counter a new advance in artillery: rifling. Using this technique, shells were set spinning when they were fired from the muzzle of the gun, which considerably improved their range and trajectory.

Bastion fortifications ceased to be efficient and the concept of the stronghold was gradually replaced by defensive systems known as "entrenched camps". This change in focus led to the demolition of San Sebastian's city walls in 1864 and the construction of large numbers of forts during the Carlist wars.

The entrenched camps might be described as territories in the dominant positions of which permanent fortifications (forts) were established, capable of mutual defence (the distance between them is less than the range of their artillery) and support troops operating in the surrounding area. They were generally served by a set of centralised facilities: a military hospital, magazine, barracks, artillery, communications network, etc.

French general Raimond Seré de Riviéres (1815-1885) is largely responsible for spreading this type of fortification: between 1875 and 1895 he designed a complex defence system for France, made up of various entrenched camps (Verdun, Toul, Epinal, Belfort, etc.) joined by intermediary forts to form a continuous line of fortification of 166 forts and dozens of batteries. Another important figure was General Brialmont, who created a fortification system made up of 21 forts around the Belgian cities of Liege and Namur in 1887.

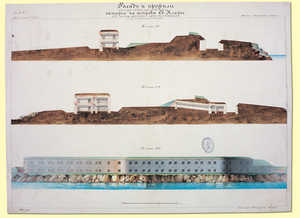

During the second half of the nineteenth century, military authorities sought to seal off the border between France and Spain, although this aim was not entirely fulfilled due to lack of finances. Nonetheless, many forts were built, including those of the entrenched camp of Oiartzun, the Alfonso XII fort on the hill of San Cristobal (Pamplona), the Rapitán fort (Jaca), the Coll de Ladrones fort and battery in Sagueta (Canfranc), St. Helen's Fort (Biescas) and the St. Julian of Ramis fort (Gerona).

The techniques used to reinforce these fortifications were soon made obsolete by new advances in artillery, and especially the appearance of torpedo grenades in 1885, whose new high explosives could be primed to explode after the shell had penetrated inside the fortifications. Firing speed was also increased by more widespread use of breech loading (cannon had previously been muzzle loaded) and, the appearance of fast-action cannons. The use of smokeless gunpowder to impel the shells also increased the range of the guns.

Steel began to be used in place of iron and bronze. At the same time, the emergence of military aviation from 1911 on, made this type of fortification all the more vulnerable.

Elsewhere in Europe, these shortfalls were countered by replacing double caponiers with counter-scarp coffers, the large-scale use of special concrete (from 1895) and reinforced concrete (from 1910), rotating turrets and metal bells (already in widespread use in Europe by 1900), the dispersion of the batteries (such as the German festen) and underground fortifications (Maginot line, 1932-1944), but these advances were not repeated in the fortifications of Gipuzkoa.