Architectural characteristics of the towers

Somehow we have already mentioned them throughout the preceding chapters. The architectural characteristics presented by the Towers were a reflection of their history. Those who inhabited them always tried to unite functional and aesthetic criteria, even if they are not easily interpreted by us in every case. The Towers were first of all the home of the lineage, then the home of the core family it started developing after the late Middle Ages; they represented a series of "values" that they wished to communicate to the community (and, indeed, the enjoyment of which the community only recognised to a certain type of lineage or family) and as such, they were the support of a very interesting and still barely known system of symbols. The Towers also fulfilled another series of practical functions, that led to their morphology: defence and military purposes, economic and social, be it the rural or urban environment. And we should not underestimate this piece of information; they were built in a particular geographic area and by people with limited culture and aesthetic knowledge. Gipuzkoa offered restricted materials for construction; the masonry tradition in the Territory was very old (and will render as much or more fame to the children of the Province in the XVI century as the handwriting skills that even Cervantes mentioned) and provided soundness to a type of architecture that itself had a vocation of permanence.

Therefore, to refer to the architecture of the Towers means not to forget those facts, so as not to limit ourselves to the tedious listing of formal elements that characterise what we nowadays understand by Tower in the widest sense of the term (which, as will be shown, is really slack). Those elements are more than sufficiently enhanced in this book by the photographic machine that goes along with the text. The reader is already familiar with a type of style which does not require a detailed description.

In the time spectrum englobed between the XIV and XVI centuries, we will just stick to the aspects related to the construction materials, the shapes adopted by the Towers and their evolution, their structure as multipurpose houses and the external elements that defined them: windows, arches, closed scaffolds located over the top floor, etc. There are but a few significant examples remaining in Gipuzkoa and we should start by clarifying what type of building we are referring to.

When talking about Medieval Towers, we are limiting our field of observation to high houses, with the consistence and shape of a classical tower and not so much to the buildings that present a soundness and morphology that imitate those of the other ones that vulgarly receive the name of tower or even rural palace. They are usually caserios and lineage buildings of upper strata that, challenging the passage of time, have been preserved until today but that are only "noble" caserios in the construction of which (usually carried out between the XV and XVI centuries) ashlar and the building tradition of classical towers were used due to an obvious wish of their owners to emulate the lineages standing on the summit of the social pyramid. We should not forget that they were built by the same masons in the same epochs. Therefore, it is not strange that the bibliography of those times could confuse some constructions with the others (beginning by the contemporary experts themselves for whom, in the rural environment, well into the XV century, there would not be Towers but "Strong Houses" and, in towns and their outskirts, "Palaces") and that the solid appearance of a building deserved the common denominator of Tower. I also have my doubts in more than one case and admit a high percentage of a priori omissions and exclusions. May I be allowed to object that, to enjoy this Heritage, listing fundamentalism is needless and that it is good that this versatile frontier exists. But we should not forget that the name Tower was established by those who were best informed to proceed to that classification. The society of the XV to XVI centuries knew that only certain lineages or Manors could be or include Towers (as explained in the first chapter in detail, called Strong Houses before), as the capacity to have a Tower responded not only to the economic position of the lineage (more clearly in the case of urban Towers) but to the social consensus reached by its owner. And the ownership of a house considered to be a Tower was reserved to a certain type of owner.

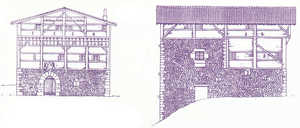

As we know, from the XIV century, the first material used was wood combined with masonry and, only later on, ashlar stone. Many of the constructions preserve remains of all the epochs and a careful observation of them is very stimulating. The foundations of the Tower can easily present a different type of stone and a more rustic style of construction; in higher floors, stone can even be replaced by ashlars in the angles and windows and the oldest walls can display reforms. The Tower was almost a "living creature" and was adapted by its owners to different and/or complementary uses in each epoch.

We can estate that, once the most critical moment of the faction conflict was over, buildings in a Tower shape were massively made of stone on their lowest floors and that the upper ones were gradually built either in stone or brick. The lopping of the Towers decreed and performed in 1457 forced the Manorials to rebuild their Manors and Towers. If the Baldas or the Loiolas used brick, the Berastegis or the Amezketas used stone, but to a lower height. Catholic Queen Isabel allowed the Lord of Amezketa up to two sobrados ( floors). Towers became shorter and there were but a few in Gipuzkoa that kept their previous impressive aspect.

Examples such as the Zumeltzegi Towers (in Oñati, site of the Gebaras, Lords of the Earldom) or those of the Isasagas (Azkoitia) or the Ysturizagas (Andoain) (both lineages of merchants) were extraordinary. And caserios like the one of Egurbideola in Azkoitia constituted, due to their volume and structure, examples of a civil architecture that was more in accordance with what we could identify as a tower than the towers themselves.We should not forget, either, that a great part of the medieval Towers would be subject to very important structural and ornamental reforms throughout the XVI century. Towers like those of Enparan or Zarautz, Loiola, or the one of Ozaeta, are significant examples of the changes in fashion or use that the houses underwent. They were transformed into Palaces of a Reinassance or Baroque style, depending on the century in which they were rebuilt or reformed. The case of the Ozaeta tower is very significant: rebuilt by Beltran Lopez de Gallaistegi Loiola around 1550 on the medieval Manor of Ozaeta, the Tower led to the Palace of a Reinassance style that Don Beltran rounded off by ordering a retable of his portrait and that of his wife, Isabel de Recalde Idiakaiz from a Flemish workshop. Saint Ignatius' nephew is a clear exponent of the change in taste and manners of the Gipuzkoan elite

The basic material with which the Towers were then built was stone, as masonry and with a growing use of ashlar. Stone gradually replaced wood on the façades of buildings, both due to its soundness as its constructive efficiency. Wood was reserved for internal distribution. Ashlar also gradually took the place of simple masonry, and was basic in the angles of buildings, windows, and different ornamental elements. The elements that supported the defensive or merely architectural structures required by the Towers had to be made of squared stone.

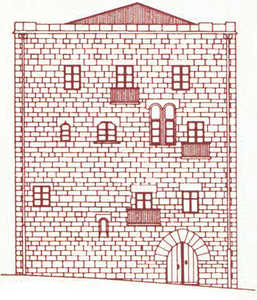

The shape of the Towers in Gipuzkoa, needless to say, ranged between the purely quadrangular (the classical Tower) older one to the most evolved and modern rectangular one. The Towers had to respect that morphology, which favoured high constructions. In certain cases, they were attached to other constructions, which granted them a somewhat amorphous general aspect.

Out of the group of Towers, their usually austere appearance might be surprising. Compared to Biscay, Navarre or Araba, Gipuzkoa has not preserved examples of purely medieval, massive aspect towers, like the Butroe Towers (before the XIX century reform), Salazar of Muñatones or Fontecha or Mendoza. Perhaps that name could be identified with what we called Strong House, based on what the documents themselves transmit, but of which we lack representative examples. The Gipuzkoan Tower is in general terms more modest in its dimensions; is not usually surrounded by other important buildings, thus resulting in a group, and barely ever keeps (if it ever did) the terminos redondos mentioned in the documentation, in the shape of a small wall or stone hedge. Private property seemed to present until very recently in almost every case that type of possession surrounding the house, be it a Tower or not. Some caserios kept it more or less willingly or materially and the already mentioned Tower of Ozaeta was built in the XVI century reserving some room of that kind. The most important building groups were the ones conformed of the combination of a Tower-house, a mill, a foundry, a hermitage... A few years ago the splendid example of Karkizano, near Elgoibar, disappeared and other cases can be traced down, like those of Alzolaras (Zestoa), Sasiola-Astigarribia, etc.

The Towers, in their external appearance, offered a simple structure sometimes ending in a row of small embattlements (Tower of Zumaia, for example) and always in a four-side saddle roof. hen ending a Tower, in Gipuzkoa a model was spread which remained in force for the whole Basque Country and became very successful and historically survived as an architectural as well as decorative solution: the use of solid cylindrical turrets or sentryboxes located in the four upper angles of the Tower and that were either based on the roof or stuck out as its pinnacles. The sentry boxes survived until the Baroque and were widespread, being adopted almost in all Towers that turned into palaces during the XVI century.

The structure used in the internal construction of the Tower was also simple; a big central wood post or beam that supported the frame-work was the solution adopted by most masoncarpenters. Be it Towers in the most strict sense of the word, or caserios or any type of building (note the porticoes in some churches as an example of that structure, today so hard to find). The wood branches were supported by the central beam, on one hand to support the floor of the different stories or sobrados, and on the other to distribute the internal space of the tower. The walls of the Tower, many times of an extraordinary thickness, planned holes or modillions or projecting ashlars on which, starting at the main beam, the real beams that support the solibos, ceiling and floor boards were supported; and, between them, the partition walls were of wood, brick or masonry; the wood onws might be the oldest, replaced by masonry due to its building efficiency. Note, nevertheless, the cunning system of "sliding partition walls" that, in some cases, the inhabitants of the Tower could enjoy due to those primitive wood structures, as seems to be shown by the traces preserved, for example, of the Laurgin Tower.

The different types of openings or holes in the shape of windows, balconies, etc., will give us an idea of the date of the construction, as well as some hints about the internal distribution of the rooms or spaces in the Tower. Windows and doors were par excellence the support of the ornamental elements of this type of building, together with the family arms or representation of the lineages through their coats of arms.

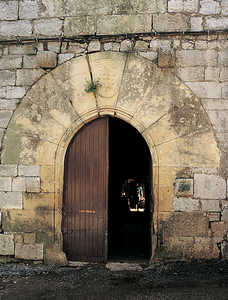

In the oldest Towers, the entrance door was usually placed on the first floor and accessed throught a stone staircase (or patin) or through a wood staircase that could be withdrawn when appropriate. Some Towers, like the Torre Luzea (Long Tower) of Zarautz, or that of Ereñozu, preserve wonderful patines. The staricase was defended from a series of loop-holes. Upon the transformation in the use of the towers and once that they lost their defensive nature, entrance to the building was performed through a door located on the ground floor; the door then became bigger.

The openings and windows also suffered a transformation in accordance with social development. From the small single arched openings, few in number in the Towers dating back from the XV and beginning of the XV centuries to the wide geminate windows that preceded ogee arches and Renaissance-type windows that fell from an arc gradually into a straight line and displayed, in some cases, abundant decoration, which was generalised through the XVI century. Inside the Tower, the thickness of the wall in which the opening was made was used to make wide seats on both sides.

In any case, the structure of all those holes which were no more than openings in the thick wall of the "rough stone and mortar" Tower was always the same. The opening was limited by ashlars of one or several pieces depending on the size of the window and usually of a lighter colour, as sandstone blocks were used; ashlars that could help support the geometric or floral ornamental motifs and, in some cases, used to carve them into the arms of the lineage or their commercial marks. It is not surprising to find an old tower decorated in the XVI century that displays new doors and windows in ashlar to replace the old rougher ones of a worse manufacture. And, from the formal point of view, the round arch model, with the ashlars resting one against the other, conforming the arch which, in the case of windows, took the ogee shape, and in most cases, the shape was carved in a single block of stone, reached a great success.

Obviously, all the aforementioned defines the architectural structure of the Towers within the wide spectrum of time that was a witness of their development. That did not prevent the same solutions being adopted for other types of rural or urban constructions that were no more than caserios of usually a lesser lineage but that never attempted to compete with the Tower which represented, both through the use of a specific construction as well as through the social and family values that society granted it, the symbol of a limited power and prestige which was limited to just a few. The most significant example is churches (Zumaia, Bergara...) which, in their construction, used all the elements described above and therefore looked more like towers than temples.

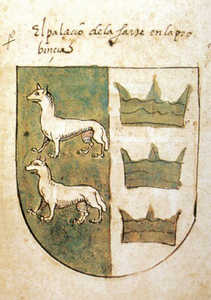

The mis-called "heraldic coats of arms", better lineage arms, usually decorated the entrance of a Tower, or one of its angles. In the Gipuzkoan case, they deserve a specific comment because they present their own peculiarities.

There were but a few Towers on which the lineage carved their family arms, although they were more common in urban Towers, on the entrance door of which the central vault-stone of the arch was carved with the commercial "mark" of the owner lineage or, if not, with a "Ihesus" anagram. The use of the arms by the members of a lineage, as their representation and symbol of their belonging to it, by the use of their particular set of symbols, of their own semiotics, seems to have been introduced at a late period in Gipuzkoan territory. Arms were preceded by the use of "symbols" by the lineage; thus, we still have those of the wolves and boiler adopted by the Loiolas, that constitued the antecedents of the quartering with the Oñaz factions used at least from the end of the XV century. The repetition of heraldic motifs, preferably wolves and boilers by a faction (Oñaz) and escallops by the other (coming from the Gebaras, by the Ganboa faction) is also a clear element that must not be underestimated.

But Towers were decorated with family arms, if they were, very late. I do not think that the custom could be dated before mid XV century and, even from the design of many of the coats of arms,it looks like they were not massively but more usually adopted by the lineages at the beginning of the XVI century, when they started being more concerned with that type of representation. We know that, by then, many merchants (like Councils themselves) used their marks or arms to authenticate the public documents that they granted, under the formula that established that each granter "each of his names he sealed with his seals". Those representations were not transferred to Towers or, at least, only half a dozen old ones have been preserved. It is only from the late Renaissance and due to the massive reception of Castilian and European fashions and through the development of a society of "hidalgos" that the transformation of many Towers into urban Palaces or of a comparable style that lineage arms started being widely adopted as a decorative element of prestige. The stylistic development included the quartered arms in which either the arms of the constructor's grandparents were combined or the solution to use the arms that corresponded to the surnames of the family estates that it enjoyed was adopted.

Usually, the design of the coat of arms depended on the skills of the mason. Thus, the best and oldes examples were from an urban background. They all displayed the clear adoption of the heraldic norms in fashion in the epoch. Both the brisures as the quarters, as well as the general heraldic design responded to the governing models. The Bidaurreta Monastery combined the arms of the Lazarragas (those of the "Garibai lineage and faction) with the personal arms of Juana Ganboa (the Ganboa complete - as daughter of the Manor Chief - with saltired orle) and all of them with those of the Franciscan Order and the complete of the Catholic Kings, at whose service - as already mentioned, Secretary Lazarraga, builder of the Monastery - spent his life.

We have a wonderful - and unique - example in which we can trace the use of the same arms by the descendants of a Manor, combined with the arms taken from other lineages or Manors through marriage or inheritance. The attached outline [vid. diagram, pgs. J relates a series of descendants from the larza Manor of Beasain (who, by the way, did not have a coat of arms). We find the larza arms in Hernani (Palace of the Elduains), in Segura (Gebara Palace) and in Amezketa (Manor of Amezketa); in Hernani and Amezketa, carved following the orders given by Juan Lopez (through the attached inscription we know that in 1484) and his sister Urraca Velez de Amezketa, combined with those of the Manors of Altzega and Amezketa the first of which he was the heir, and the second, the daughter (the former in pallets, the latter in split); in Segura, quartered (carved so that we can date them around 1485) by Nicolas Gebara with two quarters from his father, of Gebara (scallops and factions loaded with water-bougets) and those of Larrastegi from his mother. Furthermore, in the case of Hernani, the two precious coats of arms (whose quality and late medieval design were fully European) preserved on the lintel of the door came from the medieval Tower that occupied the Manor in which the present wonderful Palace was built and represented the arms of the Elduain-Altzega couple. Halfway through the XVI century, Bachelor Amador Lopez de Elduain (friend and classmate of Iñigo de Loiola and Francisco de Javier in the University of Paris between 1528-30) used them, combined in a 5 "quartered" coat of arms in the chapel that he had built in the parish of Hernani. In said parish, the arms of the bachelor and those of his second wife, Barbara Anizketa, both of a Renaissance style were confronted.