Life and work in the farmhouse

The family area

Although these farmhouses were large in size, with an average ground plan of 300m2, the area traditionally reserved for family life was often so small that it covered just a fifth of the overall area.

The living area was always on the ground floor, and it is only over the last hundred and fifty years that bedrooms have been installed on the second floor. In single-family farmhouses the living area was installed either in the front part of the house or along the length of the side looking down into the valley, while in two-family houses it was always at the front.

The house was divided into two parts: the kitchen, sukaldea,and the bedrooms, logelak. The kitchen, which was next to the entrance and usually occupied the front corner of the building, was the centre of the farmhouse and, especially, a place for talking; it was the place where the family would get together, where visitors would be received, where the women would weave in the evening and where local events would be ruminated upon during the day.It was also where weddings were organized and where the most ancestral rites of the popular Basque culture were carried out.

During the 16th and 17th centuries the fire would be lit on a slab in the centre of the room, over which the pothook would be hung. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, low hooded chimneys standing against the wall became widely used and, in the century now coming to an end, industrially manufactured metal stoves, or economicas, were installed, which meant the saving of a lot of fuel.

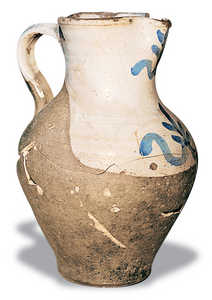

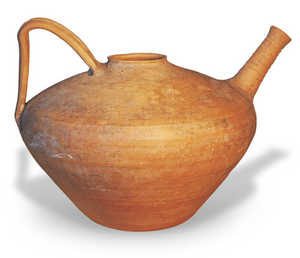

The main piece of kitchen furniture was the zizaillu or izillu, a bench with drawers under the seat and a high back to which a folding table was attached. The dishes, very modest, included objects of rustic pottery, wood and sometimes pewter: pots, jugs, buckets, pedarras (pitchers), earthenware bowls, jars and plates.

Each farmhouse had three or four beds, each with their respective double linen covers, and there were always several carved chests for storing clothes. Until the mid-19th century, the bedroom was normally a single room which, at most, was divided into two different rooms. There are fewer and fewer houses which still have the old common dormitory with its row of built-in sleeping areas, no bigger than the bed itself, and separated by a simple linen curtain. The concept of privacy has changed greatly since then.

The area for livestock

Even more than the crops, domestic animals, and especially cattle, were considered as the farmhoues’s symbol of wealth.

Nothing was more precious for Gipuzkoan farmers than to have a good pair of strong and healthy oxen. Even in fairly recent times, when animal traction had become a thing of the past and oxen fought against being tied to the yoke through lack of habit, many of the “baserritarras” refused point-blank to go without their beautiful oxen.

More than half the ground floor of the building was reserved for cattle. Each animal had a stall shaped like a wooden box through which it would stick its head to get food, and it would have a straw and fern bed on the floor which would later be used as fertilizer. Until the mid-18th century, two of these stalls would be installed in the wall next to the kitchen with two sliding communication hatches. This meant that a check could be made on cows about to give birth or on the bravest oxen, whose gentle heads were a usual part of family discussions.

The stable was entered directly through the porch, when there was one, but there was almost always an extra side or back door which permitted rapid ventilation and a much more practical transit of people and animals. There were no windows in the stables, but narrow breathing holes which look like loopholes. Nor were there partitions, even although some animals, such as pigs, were kept in a corner of the same room. In ancient times, when the pigsty was much more abundant, it was quite normal to have them running loose near the house or group the herds toghether in communal oak and holm oak forests.

Some farmhouses in the mountains areas of Gipuzkoa to the east of the Oria river used to own huts in the proximities of high pastures. These huts served as small stables for keeping sheep and cows, as well as a supply of straw and fern. Their numbers have slowly reduced over time but they used to be very common. The ones nearest to the valley or inhabited centres were converted into houses during the disorderly expansion of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the least accessible were gradually abandoned.

Storage space

Each of the products harvested by the Gipuzkoan farm worker had its own specific space within the architecture of the farmhouse. The whole upper floor was dedicated to storage, and in many cases there was also a semi-basement beneath the house.

Over the stable there was a straw loft, or mandio, where grass, hay and straw was kept for the livestock. An open hatch in the wooden floor was very practical for being able to pitchfork down the amount required at any given moment. Since the 19th century, and where the lie of the land permitted it, an exterior ramp has been added to the farmhouse so that loaded carts can enter into the straw loft. Before this, hay was thrown up and through a high door, a job which required great effort.

On the front part of the upper floor was the attic, or sabai, which was well marked off with wooden separations or rubble walls, and sometimes with a small, open balcony over the façade. This area had several funtions, which have changed over the years. It was originally used by some 16th century farmworkers as a wheat granary and for storing apples or fruit which they planned on keeping throughout the year. With the appearance of corn at the beginning of the 17th century, it became the ideal place for curing the cobs and stopping the grain from fermenting, by laying it out on the dry floor and airing it well. This area had to be increased in the 19th century in order to leave a space for beans and potatoes, which also needed a dry and ventilated surface. It has also been used as a dovecote, clothes-dryer and attic for general storage.

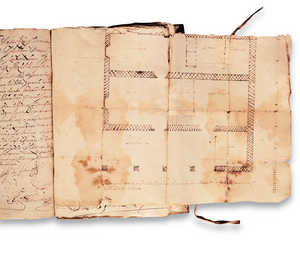

The old wooden chests for storing wheat were also kept in the granaries and basements. The elevated granaries, known as garaixe, were already part of the Basque farmhouse in the 14th century but, like all mediaeval country buildings, they underwent a drastic change at the beginning of the 16th century, They had a short life, since they were no longer being built in the 17th century, and they were probably not introduced outside the western valleys of Gipuzkoa, in spite of the fact that one in Agarre, recently restored, is one of the most impressive specimens still standing in the whole Peninsula.

The basement, upategi or iputeixa, is one of the storage areas which best identifies some models of Gipuzkoan farmhouse with respect to other varieties of the Basque country house. These were built during the 16th and 17th centuries, on land with steep slopes where they were inserted under the downhill side of the building. These were dwellings with wooden roofs and earthen floors, with their own outside entrance, which were ventilated by means of two very large, narrow windows. This is where the aromatic cider barrels, always present in any Gipuzkoan house, were lined up in days gone by, and there was still space for grain chests. These basements have presently lost their noble original use and are now used for compost heaps or as secondary stables for sheep, rabbits or hens.

The work area

The traditiional Gipuzkoan farmhouse was a tool and a permanent work area. Livestock was raised and harvests stored in one single closed and compact building, where a great variety of domestic objects were also made to satisfy some of the basic family needs. Many of the handicrafts carried out here, such as basketwork, weaving, carving or capentry, didn’t need a specific area, but could be comfortably carried out in the kitchen or in the shade of the spacious porch.

However, the farmhouse also had certain areas which were especially designed for carrying out one specific job, such as a mechanical task related to the agricultural cycle; these were areas and structures which conditioned the whole architecture of the farmhouse during certain periods in time and were linked to the elaboration of a specific product. The most important of these were the press house and the threshing floor.

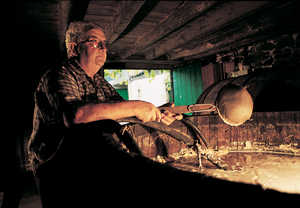

In farmhouses dating from the 16th and first half of the 17th century, the press house, or tolare, was a huge wooden machine which occupied the whole length of the house on both levels. These devices, which were used for making cider, were based on the principles of primitive Roman presses and consisted of a thick horizontal beam of up to twelve metres in length which would be lowered by an enormous wooden screw unti it flattened the mass of apples beneath it. There are no whole suviving presses, but the posts which controlled the mechanism still support dozens of the oldest farmhouses in Gipuzkoa.

- Spindle or axle (ardatza).

- Loft.

- Beam (puntala).

- Double lintel.

- Height regularing pillar (berria).

- Straw loft.

- Apple pulp.

- Trough.

- Vat.

- Stabel.

- Weight.

- Cooker.

- Fire-break door.

- Bedroom.

- Basement.

- Firebreak partition.

The pressses invented towards the end of the 17th century were still being made from wood, but they were much smaller and had several screws for direct pressure. Later, in the early 19th century, another kind of press started spreading which was smaller, could be taken to pieces, with a central iron worm and automatic mechanism, and which can be seen today on many of the local farms.

As with pressing apples, suitable areas were creted for threshing wheat –which was linked to the history of the Basque farmhouse for more than five hundred years. The Gipuzkoan farmworkers of the past didn’t use threshers to separate the ear from the grain, but used either a threshing flail or would hit the sheaves directly off the stone flags on the floors. The preference of carrying out this delicate operation under shelter from bad weather brought about the construction of large paved porches, atai or aterpe, which were built along the width of the house. The first, and most primitive, were porches with wooden posts but, half-way through the 17th century, elegant structures started spreading form the Alto Deba with four and five ashlar arches which were successfully copied by the most outstanding farmhouses in the area. Due to having been built during the previous century, many of these high-quality buildings didn’t have these new covered threshing floors, and so they added a porch to the front façade, since this also brought importance and nobility to the image of the ancestral home. Today this emblematic aspect is more highly valued than the primitive function from which it originated.