How the farmhouse was built

Master carpenters and stonemasons

All the ancient farmhouses in Gipuzkoa were built by professional master carpenters and stonemasons, who worked uner contract for the owner and were helped by a team of skilled workers and servants.

The owner of the house would discuss the general characteristics of the building and the amount of money which he was prepared to invest with the master, and would often collaborate by transporting part of the necessary stone, wood or lime to the work place with his team of oxen.

The important part played by craftsmen builders in the creation of popular Gipuzkoan architecture gave them a sturdiness and quality uncommon to European peasant homes. Likewise, and since the masters also worked in the building of curches and noble houses in the country, it was inevitable that they be affected by the fashions of the time, which resulted in the farmhouse, without losing its autonomous and functional character, becoming especially sensitive to the different artistic styles of each historical period.

During the 16th and a good part of the 17th century, the master who planned the work would be in charge of directing it step-by-step until its completion, which was celebrated with a huge banquet. However, around 1650, functions were being split and a new kind of master appeared who would think, take decisions and sometimes make drawings of the kind of farmhouse to be built, but who would later leave other masters or lower-rate skilled workers to take care of the actual building of the idea. When the house was finished he would come back to look it over with an expert on the subject and decide how much should be paid to the contractors, depending on whether they had been capable of following the plan properly or not.

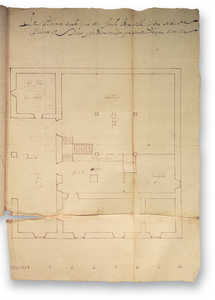

The first qualified architects, who started appearing during the last ten years of the 18th century, were responsible for planning large farmhouses, a forerunner of which is the house of Iraeta in Antzuola, designed in 1796 by the Bergara academic Alejo de Miranda.

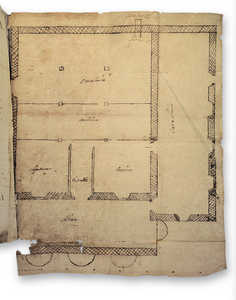

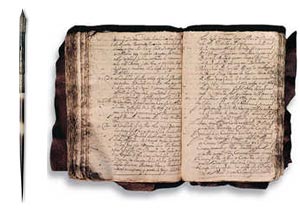

Construction contracts and design

During the 16th century, a simple verbal agreement was sufficient between the proprietor and craftsman builder for him to start working according to the orders he received. It was often the owner who, as the most interested party, followed the work at close range and took decicions about where to buy material and the amount to pay the labourers.

The labourer didn’t interfere in technical aspect, which were part of the profession learned by the master, but he could collaborate in the taking of basic decisions, such as the most appropriate orentation of the farmhouse façade, which was invariably directed towards the morning sun.

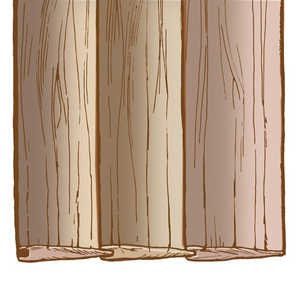

The end quality had to be high and the construction process was extremely laborious; so much so that it could take as long as two-and-a-half-years. They had to cut down and drag gigantic oak trees, saw them to different sizes, shape them and join them together at different heights, hoisting them up by hand with the help of rudimentary pulleys hauled by oxen. The stone had to be quarried with hammers and handspikes, broken down into small pieces with a quarry pick , transported in carts and cemented with sand and lime, which would previously have been cooked in a wooden oven, and more loads of stone. If we add the making of six or seven thousand tiles and several hundred hand-cast iron nails with the effort which implied, plus the tiring job of collecting all the above-mentioned elements in an orderly fashion, we get an approximate view of the immense flow of human energy which went into building the first generation of Gipuzkoan farmhouses.

Building a solid farmhouse in the mid-16th century cost about the same as buying twelve oxen. A thrid of the estimate was paid prior to the job being started and a second when the roof went on, but the last third, which should have been paid at the end of the construction, was always delayed and was paid over several years in the shape of small amounts of grain, some cash, a farm animal or several loads of wood.

Since the mid-17th century the contracts for constructing farmhouses were drawn up in writing before the village notary and quite often the master builder would draw up a plan o traza and a list of technical conditions which the hired stonemasons and carpenters would undertake to respect. Beautiful buildings were still being built but more and more models and categories were appearing: large family farmhouses with ashlar arches and shields, which incorporated all the artistic novelties of the time; modest timber and stone farmhouses; solid double farmhouses for tenants and small farms made from planks of wood and rubblework for the a few heads of livestock for the owner. The masters offered a different solution to every kind of requirement, but they always maintained a certian stylistic homogeneity according to the cultural and ecological unity of the Gipuzkoan countryside.

Constructions materials and techniques

Several different possibilities of combining the materials offered by the land were tried out during each of the historical periods in the life of ghe farmhouse. Using only three basic ingredients: oakwood, sand or limestone, and clay suitable for making tiles or bricks, which were expertly mixed using different techniques and proportions, a select menu of more than ten different kinds of house could be offered.

In Gipuzkoan farmhouses- which generally stand on a rectangular ground plan- the back and side walls are always in rubblework. However, the façade, which is the mark of its identity, can be closed with vertical wooden planks, with stone or with a trellis of small beams set out in a geometric, pattern. This last alternative offers two possible variations for filling in the spaces between the beams: either with small rubble or solid bricks, the latter becoming fashionable towards the second half of the 17th century.

The age and technique use in constructing the farmhouse are often best seen from inside the house, and more specifically in the hay loft. Many have a thick dividing wall, but, in those which were built prior to the mid 17th century it is more usual fo find a framework of enormous pillars which go from the floor to the roof through the wooden ceiling. If the house was built before the second half of the 17th century or at the beginning of the 18th century, the structure may include many natural tree forks and also curved arms to support the horizontal beams. During the later periods wood lost its importance as an element of support and was used mainly for floors and roofs.

Popular carpenttry in the 16th century attained extremely high quality, and is easily recognizable in Gipuzkoan farmhouses because it used a sophisticated technique of lateral joints with curved silhouettes similar to a bird’s open wings.

Carpentry from the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th century is completely different but equally attractive, due to the tree-like shapes of its prop and stay system. It is often possible to see the marks of assembly made by the master who built the structure on the joints between the different parts.

Partitions between the different rooms of the farmhouse have also been built in several ways over the centuries. At the beginning of the 16th century, these were simple separations made from jointing boards. Next came interwoven strips of wood covered with mortar and, by the late 17th century, brick and rubblework walls were taking over to become, in time, the most popular